Modern organisations operate within an environment of change. There are all sorts of factors that change within this environment – for example, the market price of products and raw materials, the level of competition, market opportunities, changing government legislation and, of course, technology.

This case study focuses on the way in which the oil company, Chevron, developed flexible solutions to enable it to cope with the environment of change. In particular, it shows how Chevron has successfully developed flexible decision-making for the development of its North Sea Alba Field which lies 130 miles to the northeast of Aberdeen.

The study emphasises the way in which Chevron has progressed from a slow moving system of communications, based on functional lines in sequential stages, to an improved way of working, based on decision-making in empowered interdisciplinary teams. This approach allows quick, incisive thinking and adoption of appropriate technical solutions to oil extraction.

Introduction to the oil industry

The oil industry is one of the major sectors of the UK economy, employing, directly and indirectly, 380,000 people. Currently a fifth of all industrial investment in the UK (£4 billion per annum) comes from the oil and gas industry. Britain’s offshore industry produces some 80% of the country’s total primary energy (but generates only 3% of the UK’s atmospheric emissions of carbon dioxide and methane). £150 billion in oil and gas taxes has flowed into the Inland Revenue since 1970. Oil by-products provide the basis for many modern products – cosmetics, detergent, contact lenses, coatings for pills, non-stick pans, CDs, fertilisers, fabrics, paint and insulation materials for the home – to name but a few. The North Sea oil fields have made one of the most significant contributions to the UK economy over the past 25 years.

The oil industry is split into a number of upstream and downstream activities. Upstream refers to the raw material end of the business and includes all activity directed at the finding and production of crude oil and its delivery to the refinery. Downstream refers to all activity directed at the manufacture of refined products and their marketing and delivery to customers. This case study focuses on the decision-making processes at Chevron, which operates only upstream in the UK.

Vision

Chevron Europe is part of a global organisation, Chevron Corporation, which is the sixth largest oil and gas company in the world. The Corporation employs 40,000 people world-wide and produces over 1.4 million barrels of oil and liquids per day. (1 barrel of oil = 42 US gallons or 35 Imperial gallons). Chevron (jointly with Texaco) was the first company to drill in the North Sea, in 1964.

As part of the much larger Corporation, Chevron Europe is expected to fit in with the wider global goals of the parent organisation. Its vision is to be the petroleum company of choice in countries where it has significant operations, namely UK, Norway and Ireland. Chevron Europe needs to be successful because, like any other part of a large organisation, it needs to compete for investment funds against projects in other locations, e.g. Kazakstan, West Africa, etc. Chevron Corporation will assess the proposals put forward by its subsidiaries for funds for new projects.

Introduction to Alba

North Sea fields are rarely developed by a single operating company. The cost of exploration and development alone generally makes this infeasible. However, joining forces with other oil companies is not solely a matter of cost. The collective wealth of experience and ideas that can be shared by forming a joint venture helps to ensure that fields are brought on stream efficiently and cost effectively. Alba is a joint venture between a number of companies. These are:

- Chevron U.K. Limited (Operator)

- Conoco (U.K.) Limited

- Conoco Petroleum Limited

- Fina Petroleum Development Limited

- Petrobras U.K. Limited

- Saga Petroleum UK Limited

- Statoil Exploration (U.K.) Limited

- Unilon Oil Explorations Limited/Baytrust Oil Explorations Limited

- Union Texas Petroleum Limited – A subsidiary of Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO).

Chevron’s current share in the venture is just over 20%. Chevron discovered Alba in 1984 and was given Government approval for development in May 1991. The field first came into production in January 1994 and has estimated recoverable reserves of up to 400 million barrels of oil. The extracted oil is stored for export in Alba’s Floating Storage Unit (FSU) which has a capacity of 825,000 barrels of oil. Oil is then off-loaded into oil tankers which deliver to northwest European refineries.

Development

Ever since its discovery in 1984, it was clear that drilling for Alba’s oil was not going to be easy. The geology of the area was particularly difficult and the total 750 million barrels of crude oil in the field were held in loose, unconsolidated sands. To make matters worse, the reservoir was long, thin and shallow, with a large volume of water underlying the oil. However, nearly 400 million barrels of the original reservoir oil were deemed recoverable – fairly good by industry standards.

With the drilling technology of the day, one way to reach into both the southern and northern extremities of the field would have been to construct a vast central platform – and then face uncertainties over the ability to produce the heavy, sluggish oil from the furthermost points. Chevron decided on a phased development process because of uncertainties about the performance of the oil reservoir and the processing of Alba fluids.

Phase I – Northern Platform and FSU

Phase I involved the installation of a platform with integrated production, drilling and living quarters, Alba Northern Platform (ANP), over the northern part of the field, together with the FSU.

ANP was expected to produce 227 million barrels of oil from 20 production wells (of the then-estimated total 385 million barrels recoverable from the whole field). The oil was to be extracted by conventional angled and horizontal wells. This was to be supported by the use of submersible electrical pumps. Meanwhile, a number of highly deviated (i.e. at a high angle from vertical) wells are used to inject water from the platform to maintain the pressure in the reservoir and help drive the crude oil to the surface.

Chevron’s initial plan was to complement the Northern Platform with a Southern Platform which would be installed five years later. By operating from two platforms it would be possible to reduce the angle of the wells and this would reduce costs. Technology at the time would, anyway, limit the drilling radius to only 9,500 feet (under two miles).

Building an inter-disciplinary team

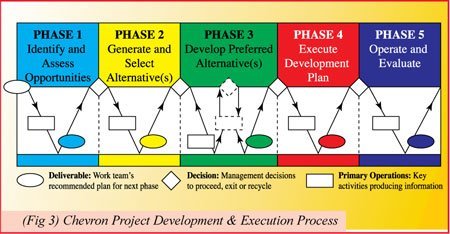

It was at this time that Chevron decided to build a small interdisciplinary team with the brief to take a thorough look at the available options. This approach was consistent with the newly adopted Chevron Project Development and Execution Process (CPDEP). (See Fig 3 overleaf). The team would provide Chevron with a creative approach – it would not simply plough ahead with pre-determined ideas.

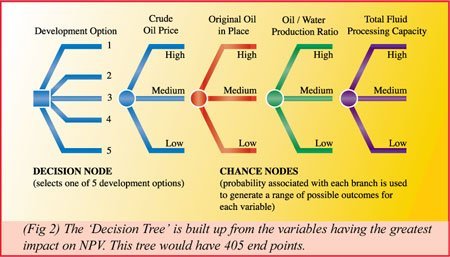

The team of five was given an open brief – to examine all the available options. The approach adopted by the team was known as Decision Risk Analysis. This is a methodology that helps to make decisions in uncertain conditions by taking a view of the probabilistic outcomes. In simple terms, this involves setting out decision trees (see Fig 2) with all the risks for each alternative decision.

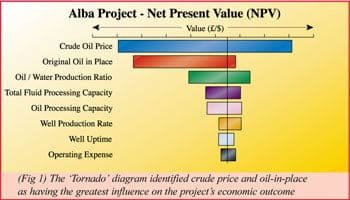

The importance of each decision is derived from the impact each variable has on the success measure (e.g. Net Present Value). This is shown in the ‘Tornado’ diagram below (Fig 1). The forecasted price of oil typically comes out on top. These risks are set out as mathematical probabilities. This new way of organising is now being adopted by Chevron worldwide and involves bringing together all the disciplines involved in a particular project at the same time and empowering them to evaluate a wide range of development options. This contrasts with the traditional way of working which would have been on functional lines, beginning with the geologists, then moving through the reservoir engineers to facilities and process engineers and finally operations.

The changing nature of Phase II

Phase II of the Alba project could have involved building the Southern Platform. However, work carried out by the project team using Decision Risk Analysis techniques indicated that there was a range of other options that were worth considering. In an industry in which technology is constantly changing, it was also clear that new approaches would present themselves as viable alternatives in the course of time.

A spreadsheet-based computer model has been central to the process used for the Alba Phase II studies. This enabled the team to simulate the range of outcomes for each of the different development options – from installing a second platform to doing nothing. In between these two extremes lay a host of imponderables. Could the southern area be accessed via sub-sea wells, drilled by a semi-submersible rig and then tied back by pipeline to the Northern Platform etc?

The team evaluated many technical solutions in search of the solution which would add greatest value to Alba’s second phase development. This was achieved by grouping them into a small number of basic development scenarios representing a wide range of different investment and business strategies. All of these needed to be weighed up to find out the optimal solution. A further problem at this time was that the price of oil was at a low level which meant that certain options would have been uneconomic. However, developments in technology meant that it would be feasible for Chevron to consider drilling wells in the southern area of the field from the existing Northern Platform, using extended reach drilling (ERD) techniques.

ERD is the single, most significant advance in technology that has shaped the thinking of the Alba Phase II team (which had grown to fifteen people with complementary skills in petroleum engineering, geology, facilities design, production and economics). As ERD has developed, so has the distance over which it can operate, enabling more oil to be accessed from the same platform.

Chevron’s project development and execution process

The process which Chevron has created for project development and execution is set out in the illustration below. Chevron was able to use this approach in the development of Phase II of the Alba field. In analysing this phase, the project team was able to narrow down a range of alternatives into an optimum solution:

- 21 options were identified for further study

- 4 failed on grounds of technical feasibility

- 9 were favoured

- 4 failed the economic hurdle

- 5 remained for further study, including a floating production vessel and building a sub-sea production centre.

After further analysis, the final option selection was between upgrading the original platform or building a second, bridge-linked, platform to the Northern Platform. The chosen option was a ‘retrofit’ to upgrade the original platform to handle increased production.

Phase II was divided into two stages, IIa and IIb, in order to introduce new platform facilities. Phase IIa of the Alba project involved installing a new 300 tonne production module. This was carried out in July 1996. New technologies were employed including the utilisation of an ERD programme, the first time that such technology had been used in the North Sea. ERD enables the furthest reaches of the field to be tapped with some wells nearing 5 miles in length. Phase IIa of the project increased oil handling capacity from 70,000 to 100,000 barrels per day.

Phase IIb is planned for completion in December 1998. This will sustain production levels and lessen the rate of decline by increasing fluid handling capacity from 240,000 barrels to 390,000 barrels per day. This phase involves adding additional modules to the Northern Platform. (See picture below and right). It also includes improvements in the technology employed to ensure the minimisation of environmental problems. The water which is pumped into the well to push the oil out comes back mixed with oil, in addition to the water that naturally occurs in the reservoir. The separation of the oil and water is a critical requirement and a difficult task, especially with heavier crude oil like Alba’s. It is accomplished in several stages in the platform facilities to ensure that the water for disposal is environmentally safe.

Conclusion

Assessing risk

Risk assessment is a key to effective business decision-making for any large business organisation. In assessing risks associated with oil production, there are a number of variables that are controllable and therefore ranges of outcomes are easier to estimate.

For example, the controllable risks of enhancing an oil production platform include:

l Technical risks – such as the calculations of the percentage of oil recovery of a particular

discovery, the extent of the field etc. Of course, problems are bound to occur in oil extraction

which make 100% accurate predictions impossible.

- Financial risks – such as the cost of borrowing money, the range in size of investments, the time taken to pay back etc. are also relatively predictable although factors such as interest rates and exchange rates fluctuate over time. Setting clear budget targets allows for a degree of risk management to be implemented.

- Schedule risks – it is essential in developing new projects to keep to schedule. Delays lead to many additional costs and problems.

Large international organisations minimise controllable risks by employing top quality engineers, financial experts, project planners and economists. There are, however, a number of risks that are uncontrollable and these require careful monitoring. One such risk is the oil price set by the global market which can fluctuate dramatically. As we have seen, the market price is one of the most important factors in Decision Risk Analysis. Low prices will mean that marginal development projects become unviable. Oil companies therefore engage in careful scenario planning, which sets out a number of scenarios for different possible oil prices in the future. On the basis of these predictions, they are able to decide whether it is worth proceeding with new projects.

In developing the Alba field, it has been essential to consider the distinctive features of the oil itself. Alba oil has a high specific gravity (i.e. heavy) and acidity and therefore costs more to refine. As a result, its market price is lower. In summary, the interdisciplinary team found a more economical approach to producing Alba’s oil than installing a second, fully equipped platform. By successfully identifying and minimising the risks associated with developing the field, production has been accelerated and costs reduced, enhancing the overall value of the field.