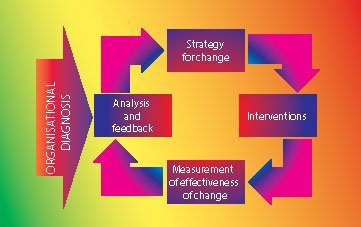

All organisations are faced with periods of evolution and revolution. As they prepare for a period of change, there will undoubtedly be immense upheaval. Within this environment of ‘chaos,’ it is important to examine the concerns of individuals and to constantly evaluate the effects of the changes. For this to happen, ‘organisational diagnosis’ should become an ongoing part of development. Analysing the results of the diagnosis provides the raw materials for a change strategy. Changes are then made and their impact is measured and evaluated. These changes can then be fine-tuned.

Tom Peters has written widely about the processes of change. Much of his work centres on how patterns change over time. In a recent paper, he pointed out that many developments, such as re-engineering, are based upon perpetual revolution and re-invention. This emphasises that change is a cyclical process in which organisations

R Griggs & Company Limited

The Dr Martens Air Cushion Sole was developed in post-war Munich for orthopaedic shoes by Dr Klaus Maertens. With his partner, Dr Herbert Funck, they patented the soles which became the top sellers in the comfort shoe market in Germany. In 1959, they decided to find a company to produce their soles for other countries. They selected a company in the village of Wollaston in Northamptonshire – R Griggs & Company Limited

Griggs, founded at the turn of the century, was already a manufacturer of the army and work-wear boots with a bias towards comfort. It began to make footwear with the Dr. Martens sole, which it branded AirWair and the Group’s success in selling the shoes led the partners to license Griggs to make the sole for the rest of the world. Today, Dr. Martens is one of the world’s best known brands and is manufactured and sold to distributors in over 70 countries. The Group employs over 3,000 staff working from in excess of 40 manufacturing sites.

Re-structuring

In 1994, the main board of R Griggs Group Ltd decided that a major re-structuring of its shoe making business should take place. Its aim was to improve control over its operational and selling activities across the world. Difficulties had arisen due to the popularity of the brand which far exceeded the Group’s manufacturing capabilities. This re-organisation, which took place in April 1995, resulted in the consolidation of all manufacturing companies under the name of ‘R Griggs & Company Limited’ with all of the sales and distribution being controlled by ‘Airwair Limited.’

This case study focuses on the follow-up to this major upheaval. At an operational review in August 1995, a report showed that considerable confusion had followed the reorganisation. Key issues included:

- unclear boundaries between managers and departments

- inadequate systems and the absence of meaningful management information

- lack of encouragement for local management to take ownership of issues under their control

- lack of visibility of the number of orders and the available production capacity.

Operational review

An operational review took place after the major re-organisation. Although it identified the main objectives of the re-organisation had been met, the review showed serious problems within business processes at operational levels, such as adverse effects on customer service, staff morale and general management control.

Re-structuring was always going to be a challenge for the R Griggs Company. In a constantly changing environment, it was important to develop the business so that products would be delivered on time. If it failed to deliver on time, the Company could lose business, despite the massive popularity of the brand. The Company’s new target markets demanded flexibility and speedy response – just-in-time supply (i.e. goods produced and delivered just in time to be sold). Such a system had to be geared to the response. This required state-of-the-art information systems so that promises made to large retailers could be fulfilled. It was, therefore, necessary to link all parts of the business process, irrespective of the size of the operation, at all levels, thus allowing data collection and evaluation.

Technology was a key element of the process re-engineering, as it allowed the R Griggs Company to improve its organisation and its response. Following the organisational review, it was vital to ensure that information technology was working to the best commercial advantage of the Group. Senior Management’s major concerns were:

- centralisation

- late deliveries

- order process reporting

- supply chain management

- production and capacity planning.

Centralisation

Centralisation is the allocation of the major responsibilities of an organisation to a central headquarters whilst avoiding central domination. Staff morale was affected when the restructuring took place as there was a feeling of lost customer contact and self-determination. It was felt that the headquarters would hand out instructions to the workforce who would have to cope with unachievable workloads and delivery schedules.

Management soon recognised that it was necessary to re-establish the team spirit which had helped the business in the past, by creating a sense of empowerment. This would make individuals more active in their organisation and encourage the use of initiative. Motivated, committed and well trained people at all levels are needed to bring about successful changes. It was, therefore, important to empower individuals within the critical chain of order processing, manufacturing and despatch. Local management teams also needed to focus upon issues such as meeting delivery schedules and stock/inventory control. In fashion markets, products have short product life cycles. The Griggs Group needed to identify ways of responding to fashion products with short product life cycles in a way which would not leave them with large stocks of finished goods.

Some distributors felt the number of orders completed on time was unsatisfactory. They also felt that Griggs could not be relied upon to discuss problems relating to capacity, what could be made and for when. Griggs needed to engage proactively with customers and not simply take orders which could not be achieved. A number of distributors commented:

‘we don’t want a progress report, we just want our shoes.’

However, there were several fundamental flaws in Griggs’ current systems. Production schedules were not put into place until materials or imported uppers had been received and even if orders were well in advance, delivery dates were not due until 2 weeks before their arrival. This made it difficult for production capacity planning. At the same time, orders were difficult to trace once production had started. Orders could disappear from monitoring processes for 2 months or more.

There was a clear need to install interactive production planning and scheduling computer systems which could track and monitor an order against a plan.

Supply chain management This system was outside the control of computer systems and was also in urgent need of support. As Griggs was constantly behind with its order book, it was difficult to appreciate the size of the problem. For example, if the backlog of orders was cleared, there would then be shortages of materials to make shoes.

A Materials Requirement Planning (MRP) system was needed to enable Griggs to take control of its supply chain. The aim of the MRP system was to provide a better way of managing diverse raw materials feeding many production sites. It was also necessary to look at stock holding policies so that the most efficient stock profile could be established together with new policies and practices for order management.

Production/capacity planning

Production capacity is what can be produced over a 39 hour week. Without a planning or scheduling system, it was impossible for Griggs to plan production efficiently. Staff were often losing customer orders until the first stage of production. Occasionally, urgent deliveries were rushed through as priority jobs. A production planning /scheduling system would help Griggs to gain control over the order book and work in progress.

The Review highlighted that systems were completely inadequate for the purpose of change. There was a clear need to develop a Management Information System to improve the control of the order book and deal with the production planning process. Dr. Martens’ strong brand image provides Griggs with a platform for substantial growth. Without reengineering the business processes, capitalising on the brand name would be impossible. The way forward was to create a suitable fully integrated system to provide a sound basis for management control and performance measurement, not only of its own operation but also that of its suppliers, distributors and product sales.)

Performance

Griggs began implementing the report’s recommendations. The area which required the most urgent attention was that of late deliveries for customers. The major cause of poor delivery performance was the mismatch between sales and production capacity. (i.e. the number of sales made and the ability to meet these sales.)

Between June 1995 and December 1996, a number of actions were taken to improve the situation. In June 1995, only 55% of orders were delivered on time. This continued to worsen through August when it reached 47% and finally bottomed out at 45% in September. This poor performance was due to making more sales than production capacity. It was pointless at this stage to continue taking orders and making delivery promises which could not be achieved in the short term. This meant that either production capacity would have to be increased dramatically or the number of orders would have to be held in line with capacity for each month.

A decision was taken to ensure that orders taken would reflect the capacity for each month promised. This immediately improved the quality of service drastically from 45% in September to 67% in October and 84% in November. Throughout 1996, further improvements were made to achieve 86% in January 1996, with a remarkable 99% in December 1996.

The planning department

In order to ensure that re-engineering was successful, the right quantity and mix had to be established to match the order book to customers’ requirements. At the same time, it was important to establish an order routing system which would take into account the different capacities of the individual manufacturing plants. This would provide local manufacturing plants with an order portfolio to match their capabilities. Discussion and negotiation helped to establish how deliveries could be rescheduled. Two significant steps were taken:

- The order intake for September 1995 was frozen, allowing manufacturing to clear the backlog in areas with restricted capabilities.

- The available capacity mix was made known to the sales organisation. This helped provide a clear picture of possible supplies and any necessary adjustments to order intake and capacity.

The next step was to implement the electronic planning tool, ‘AutoPlan,’ which came online on 17 May 1996. This further improved control over capacity, and work in progress and strengthened communication links to sales. The ownership of order processing and production control was passed to local planning offices where control of order processing and work in progress was further strengthened.

In a fast moving environment, an electronic feedback loop allows a faster overview of operational activities. With the new tools of management in place, Sales, Central Planning, Supplies and Local Planning were best positioned to react to situations around them and to take advantage of the opportunities they presented.

Spreading risk

Rather than have one key sub-plan site with 60% of the group production capacity, it was decided to spread the risk and liability of production scheduling equally across 8 Sub-Plan offices. This reduced risk by spreading the volume over separate locations and computer systems. Under the old structure, it was difficult for staff to understand the wider planning function. Staff training was, therefore, carried out to create a better understanding of the common goals and objectives for the planning process.

March 1996

To shorten manufacturing lead times, customer orders were shown with the manufacturing site and the sub-plan office. This resulted in the ability to rough-cut plan orders immediately on their receipt, rather than wait for an expert to manually allocate them. In some cases, this reduced the time taken for an order to get from order intake to the manufacturing site from months down to one week.

April 1996

The availability of on-site manufacturing equipment determines the appropriate plant for production. A computer model was built which replicated decision making parameters and took into account the location and capacity of each plant. From this, it was possible to introduce AutoPlan into the equation.

May 1996

The time taken to process an order was then dramatically reduced. Once the orders were received by the Sales Department, they were put into the system and scheduled within 5 days.

August 1996

Implementing AutoPlan across all sites enabled Griggs to identify upper sites in the UK, the Far East or South America. Pre-determining the location of the upper source helps to improve the control of work in progress and leads to performance worldwide.

January 1997

As a result of the implementation of the system improvements, Griggs achieved a significant improvement in both customer service levels and lead-time performance. This was further improved by the introduction of a link between Sales and Manufacturing businesses, enabling the electronic transmission of orders to further reduce time and eliminate any inputting errors.

Conclusion

All organisations make plans which are designed to fulfil their business objectives. These plans will usually depend upon the nature of the operation, the capacity, the required level of customer service, the time period and the organisation’s hopes for the future.

The positive steps taken by Griggs to re-engineer its business processes have enabled significant improvements in performance by reducing lead time from in excess of 18 weeks to below 12 weeks over a six month period. Griggs has full control over work in progress and is able to provide feedback (such as the progress of orders to customers on a weekly basis). Griggs now has an accurate forecast of the despatch date.

This case study shows that planning is an ongoing process of continuous improvement. Where changes take place, it is important to evaluate performance so that further modifications can be carried out where necessary. Over the last 12 months, production at Griggs has increased by a staggering 20.25%. With the new changes and systems in place, the company has forecasted an increased volume in excess of 40%, based on the 1995/6 figures, for 1997/8.