This study focuses on the way in which Philips has transformed its organisation and culture in order to flourish in the modern competitive world. Organisations today operate within an environment of change. As this environment is so dynamic, it is crucial for organisations to constantly ‘reinvent themselves.’

The biologist Brian Goodwin drew a parallel with the natural world when he said of organisms – “what you do not want to do is to get stuck in one particular state of order.” It is important, therefore, to continually adapt and move on. Nowhere is this more true than in the modern business environment, where today’s technology becomes out-of-date within a short span of time and in which there is intense global competition as firms jostle for the new “huge markets” that are opening up.

Turning things around

Philips is one of the world’s leading electronics companies. Its products are diverse and range from coffee makers to silicon chips, from recordings of Mozart’s symphonies to cancer screening systems. Philips has been at the forefront of electronic innovation since 1891, registering some 65,000 patents and has been responsible for many of this century’s greatest, most useful products:

- Electric Shaver

- Audio Cassette

- Video Cassette Recorder

- Compact Disc

- Energy Saving Lamps

The 1980s was a significant period for the electronics industry over which enormous changes took place worldwide. These included:

- a period of high growth for the consumer electronics market.

- innovative new products were introduced, many driven by Philips, such as VCRs and CDs.

- the actions of newer competitors, many of which were entering the electronics market for the first time, were underestimated.

This rapidly changing industry was signified by better quality products with higher reliability and value for money. Many of the competitors, particularly from Japan, had advantages over Philips and this was particularly marked in TV sets, a traditional Philips marketplace. These Japanese companies gained economies of scale to provide them with a volume advantage, which enabled them to reduce their prices. The net result was that many well-established companies were simply swept aside, such as Thorn and RCA. This meant that only Thompson (in France) and Philips were left as major consumer electronics companies in Europe.

This was a difficult time for Philips. Over this period it continued to innovate, which helped it to survive many of the threats and challenges to its competitive position, but barely grew. New products such as the Video 2000, a video system developed to compete with Betamax and VHS videos, failed because Philips had begun to lose touch with the market. Market share was falling, as were shareholder returns and share values, which meant that external investors and analysts were becoming more critical.

There was a sense of complacency inside the company – ‘we will survive because we always have and we are Philips!’ The warning signs were largely ignored. Approaching 1990, the company was faced with a serious financial crisis, posing a real threat to the future of the business. The crisis triggered a change of leadership with the appointment of Jan Timmer as Chairman, who embarked upon a reappraisal of the inefficient structure of the company.

Benchmarking performance

Jan Timmer called the top 100 managers of the company together for the first time, which included the Board of Management, Product Division and Country Managers. They decided to benchmark the performance of Philips against their competitors. This involves comparing key indicators against those of other organisations. They were forced to conclude that drastic changes were required as Philips’ performance did not measure up to the competition. Three main steps were initiated:

- Restructuring and cost-cutting. The first and most painful step was to do more work with fewer people. Changes were to reduce the number of staff by around 15%, roughly 45,000 people. The changes also involved product rationalisation. The company was simply involved in too many product areas and the business justification for this was weak.

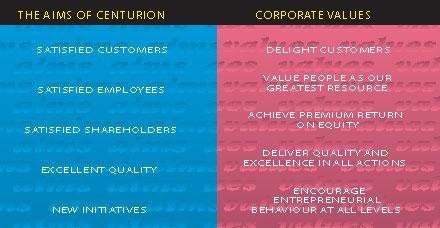

- Creating a movement for change – the Centurion programme. There was a need for a fundamental change to the way the business did things in order to get a reasonable return on capital employed. At the heart of this was a return to the basic principles of cost management which involved making products which customers wanted to buy and earning a margin. There was also a need to increase the accountability of individual business units. At the same time it was important that individuals should become aware of customer needs and then recognise the need to achieve world-class performance. Throughout this period the establishment of benchmarks helped to identify and sharpen activities so as to achieve this. ‘Operation Centurion’ led to the creation of a smaller business with more focused activities, its central theme though was to influence the way Philips was managed. New styles and attitudes to management were needed.

- Implementing change. Change projects were developed at all levels from corporate-wide task forces at the top of the organisation down to local change projects on the shop floor. For example, company-wide task forces introduced ‘Customer First,’ aimed to make staff aware that customers’ needs are the number one priority and this led to many initiatives, including ‘Customer Day.’ Local projects included reducing the backlog of orders.

First steps

The top 100 managers of the company continued the process by holding discussions and decision-making meetings with managers at the next levels (Centurion II and III) until thousands of managers were involved in a worldwide cascade of meetings.

At ground level within the organisation this then translated into “town meetings” eg: meetings between everyone in a particular unit. The heart of these meetings was the two way communication process (up and down). All employees were asked to raise challenging questions, to express their opinions and make suggestions. Managers gave information, answered questions and made decisions – on the spot.

Culture

The series of meetings and the communication process that was created by Centurion acted as a catalyst and created a framework for thousands of improvement projects by teams at all levels. At Centurion I meetings, task forces were appointed to create sweeping changes on company-wide issues. Managers at the next level made a commitment to improving business performance through ambitious breakthrough projects. Town meetings and team discussions generated a stream of local improvement projects. As a result, thousands of projects to improve business performance were launched….a cascade of initiatives!

What the Centurion project was actually doing was encouraging a cultural shift in the way the organisation operated by encouraging employees to take more responsibility for decision-making at every level – this process is described as ‘empowerment.’ Empowerment is based on the belief that if you allow individuals who are directly involved in production processes to contribute their knowledge and expertise to decision-making, then the results are likely to be much better than if everything is dictated downwards by management. The benefits of such empowerment resulting from Centurion can be highlighted by two examples:

Reducing an order backlog

At a critical point one section of Philips had £20 million worth of overdue orders. This meant many dissatisfied customers. In addition, Philips was faced with cash flow problems as they could not bill their clients. As a result, Philips assembled a project team with members from every department involved in the delivery process. The team appointed an owner for each overdue order, sorted out the immediate problems, looked for causes and found solutions. Delivery reliability improved by 75% after one year.

Shorten development time

The development of a critical new product was seriously behind schedule, so that a year’s delay was expected. At a Centurion meeting the urgency of the situation was recognised and a task force set up. The task force quickly identified key problems and set up cross-functional work groups to solve them. The new product was launched six months ahead of schedule and became a tremendous success!

A number of company-wide issues were identified at Centurion I meetings and these came to shape the focus of areas of company policy. For example, the initiative “Customer First” was set in motion to ensure that all Philips people focused their work on satisfying both internal and external customers of the organisation. Other key initiatives were:

- Emphasising ease of use as a key feature of all Philips products.

- Carrying out initiatives to develop the capabilities of managers.

- Upgrading the Philips image and unifying the “look and feel of its products.”

- Focusing on dealing with only the best suppliers.

- Taking positive measures to ensure a smooth cash flow for the business.

Evaluation

At the end of 1992 a survey was carried out of the Centurion project, involving 1,500 Philips people in 15 countries. The results of the survey were mixed:

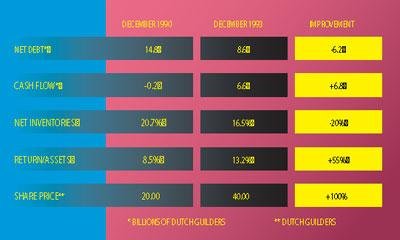

On the critical side – the evaluation showed that there was still a long way to go in managing cultural change, but at least the benefits were starting to materialise. This can be seen by a number of financial indicators.

Philips decided to move Centurion forward into a new phase of development. It was felt that the change process should be simplified so that people could understand it better. Philips decided to take fewer new initiatives and to place more emphasis on making existing initiatives work, they began to realise that looking at issues across departmental boundaries (process management) is a key determinant for success.

The new emphasis was on creating a clear set of values that would focus on the most important factors for the company:

Without customers there is no business. Therefore customers’ needs influence all of Philips’ decisions and actions. Within the organisation today there is a strong recognition that everyone contributes to the satisfaction of customers as part of a process which supplies value to the customer. Hundreds of customer surveys are carried out every year.

All of this is made possible by creating a highly motivated workforce. ‘Philips people are the company.’ Dedication, imagination and creativity bring competitive advantage. Philips recognises that people contribute their best when they know that they are appreciated for what they do. By setting up work teams, individuals have scope for growth and development within a framework of mutual support. Employee surveys have been carried out throughout Philips from 1994 onwards.

Philips has set out to create excellent value for customers by setting up a detailed quality framework to systematically assess business performance. In terms of profits, financial results are checked at every level and in all units of the organisation. In terms of enterprise, Philips is continually finding new ways to serve customers, improve quality and make money.

Communications strategy

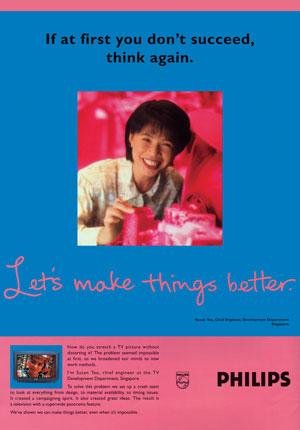

In September 1995 Philips introduced “Let’s make things better,” its new global communications strategy. Philips’ image as a provider of technically advanced, quality products remains relatively strong. The company believes, however, that its new “Let’s make things better” campaign can further strengthen brand image in the eyes of tomorrow’s consumer. An essential aspect is that this strategy is not about communicating differently: it is about thinking and acting differently as a company and as individuals.

The words “Let’s make things better” embrace a duality: a desire to make better things through innovations and products so that people will say “I want to buy that”; and also a commitment of the entire Philips organisation to continue to make things better and affect people’s lives positively.

Today, Philips operates in a way which is quite different from the way it did in 1990. Today the emphasis in Philips is very much on its people, who are the driving force behind an organisation which is geared towards the customers and providing quality products. Today it is not technology but people who are at the heart of Philips. Its advertising is, therefore, more than just a campaign. It is not surprising that the advertising centres on the people who personally “make things better” in their work; the story is that of Philips as a whole – the values and beliefs of a winning company, with an unequalled record of innovation.

People today have begun to look at Philips not as just another manufacturer, but as an organisation made up of people with a mission, with know-how and ideas that make a positive difference in their everyday lives.

Conclusion

After five years of focusing on internal restructuring to make Philips lean and competitive, it was felt that the time was right to “go public” with a simple, hard-hitting expression – “Let’s make things better.” What this statement says about Philips is that at Philips:

- they strive to be the best at what they do and refuse to accept that their best efforts cannot be bettered.

- they value the contribution of each individual and the power of a team with shared ideas and beliefs to make a real difference.

- they recognise that as a world-class company, Philips has a wider responsibility to customers, partners, local communities and shareholders, than simply meeting the needs of the balance sheet.

- that they accept that Philips must continually evolve to meet the changing needs of customers and that they are prepared to put themselves and their reputation on the line to do so.

“Let’s make things better” is the new company theme worldwide. From now on Philips will speak with one voice and show one face to all target audiences across all product groups and regions.