In the late twentieth century, major corporations in modern industrialised economies have recognised the need to add value to their products. Adding value means making the product more desirable and valuable to the consumer. Consumers want to buy those goods and services which best meet their wants and needs. Nowadays, these wants and needs are becoming increasingly sophisticated. Today’s consumer, for example, does not want ‘any old pair’ of trainers – the consumer wants ones which incorporate the latest gimmicks and technologies and which, of course, carry a prestigious name. The intelligent organisation is therefore continually seeking new ways to add value in the production process in order to influence the buyer’s perception of the product in a favourable way.

The main reason why it is important to add value is modern technology. Technology means it is relatively easy for producers throughout the world to manufacture and sell standard goods and services in bulk. Automated factories are now relatively easy to set up and modern communication and distribution networks have opened up many areas which, until recently were seen as distant and remote. It is therefore relatively easy to produce standard textiles, chemicals, engineering components or television sets and, most obviously, car prices reflect this. In order to keep ahead of the competition, it is now necessary to move beyond the standard unit of production – it is necessary to produce something that is a bit special. This is why companies that can add more value than their rivals are able to lead the field.

This case study focuses on how ICI, an intelligent, modern company, has altered the way in which it does business in order to create more value for customers. It examines the transformation of ICI and the rationale behind the company exiting commodity chemicals and moving into speciality chemicals. Traditionally, ICI was one of the world’s biggest producers of basic industrial chemicals such as polyester, titanium dioxide and ammonia. It invented polythene and perspex. Today, it is a leading manufacturer of exciting new products such as snack flavourings, perfume fragrances and adhesive for microchips, as well as being the world’s leading decorative paintmaker. By the end of 1998, most of the industrial chemicals division which, only ten years ago, accounted for more than two-thirds of ICI’s business, will have been sold to other companies – taking most of the huge plants familiar to the skyline out of ICI’s ownership.

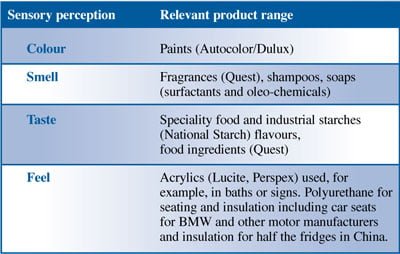

- The vision of the new ICI is that it will have a spectrum of products, which stimulate the senses, whether of colour (paints), taste (food flavourings), smell (fragrances) or touch (polyurethane and acrylic materials).

- The result is a collection of consumer-related businesses stretching from Dulux paint, Cuprinol and Polyfilla, to personal care products, fragrances, flavourings and highly specialised adhesives.

Creating a strategy

Modern business organisations live or die according to the strategies they formulate. Strategies are the frameworks which define the direction a company is moving in. Strategy is concerned with setting out the core products and services that form the heart of the organisation, the markets the organisation will operate in and the key resources required to put strategy into practice.

Since its foundation in 1926, ICI had been a major producer of commodity chemicals. In the past 25 years, this market has become increasingly difficult to operate in because competition is fierce, prices are subject to wide cyclical swings and profits have been reduced. In recent years, prices have become global and advantage has passed to American companies with large home markets and low energy costs, and Asian producers with growing markets and less pressure for large profits. When the economy is booming, it is possible to sell commodity chemicals profitably. However, in a recession, losses are almost a certainty. Successive Chairmen of ICI have each spent time considering how best to restructure the organisation. A major problem was that as soon as an area of competitive strength was identified, rivals quickly moved into this market and depressed prices for everybody (a classic feature of competitive markets). This occurred in titanium dioxide, explosives and advanced materials for use in high performance cars and aircraft – a series of products which ICI saw as winners but for which the competition moved in very quickly.

The market

Another problem for ICI was that it had a relatively small home market to rely on – in comparison with rival US and German companies. If you have a very large home market, then you can make good use of economies of scale to give you a competitive edge in selling in world markets. Unfortunately however, Britain accounts for just 2% of world chemicals demand. The solution was to carve out a position of supremacy in high value added sensory perception products. This is where ICI was to place its resources in the late 1990s.

ICI aimed to change its cost base and achieve real productivity improvements. At the same time, it wanted to make the company more international (i.e. less concentrated on its traditional markets with countries that were formerly part of the British Empire). In business terms, ICI was seeking to reposition the group – restoring and building on its respected science base, establishing a powerful position in all the key growth markets and following a customer focused approach, capable of creating sustainable value.

Transforming the business

How then did ICI set about transforming itself? ICI decided to create a new portfolio of businesses in areas where it is difficult for rivals to set up, describing the new businesses as: ‘ones where you can’t simply spend £500m to set up a large production plant to gain entry to the industry overnight’. Rather, ICI has moved into a range of new products which depend on high levels of skill and intelligence. These are products which require wisdom, expertise and accurate research and development based primarily on the requirements of customers. ICI is therefore doing what a number of business gurus in Europe and America have been suggesting – building the intelligent organisation that produces highly sophisticated products that address the needs and requirements of modern sophisticated consumers.

ICI is therefore taking a very bold leap. It is selling less profitable sections of its bulk chemicals business and channelling its resources into building up existing parts of its business and acquiring new businesses that focus on its new core lines. This has involved a staggering £9 billion redistribution of assets (acquisitions and sales) in the year leading up to April 1998. In effect, ICI has asked for a ‘redeal’ in the cards it is playing with. Instead of playing a hand containing a number of fours and fives, mixed with the odd nine, ten and picture card, ICI has been able to choose its own hand – one with a number of potential aces and trumps.

Acquisitions

In order to establish its position in its new core areas, ICI has carried out a number of major acquisitions. In 1997, ICI completed a £4.8 billion acquisition of Unilever’s speciality chemicals business. The principal businesses acquired were:

- National Starch, a world leader in industrial adhesives and speciality starches. National Starch is a company acknowledged as a leader in technology. It produces a range of products with many practical applications. Most of its products are based on natural starch and are well suited to increasing concern about the environment. Almost all processed food contains some starch products.

- Quest, one of the world’s leading fragrance, food ingredients and flavours companies, with particular strengths in new product development and applied bioscience. Fragrances it has developed include Thierry Mugler’s Angel, Eau de Rochas, Le M.le and many others.

- Unichem, is a global leader in oleochemicals. Its products are based on a broad range of oils and fats, mostly drawn from vegetable sources. They are used for a wide range of applications including personal care, industrial and household cleaners, polymers and lubricants.

These were all businesses with high profit margins, high potential for growth and a responsible environmental profile. They were all value added businesses which met the sophisticated needs of advanced consumers. In 1998, ICI added Polycell, Hammerite and other do-it-yourself products, bought as part of the European division of Williams (a £350m acquisition). Later in Spring 1998, ICI spent a further $560 million on Acheson Industries, an American company which makes electronic materials for products including switches in computer keyboards and films for medical devices.

ICI’s growth in these product areas is complemented by a spread in its geographical operations (i.e. globalisation). For example, National Starch’s position as a pre-eminent US speciality chemicals company together with its strong commitment to emerging markets in Asia and Latin America has reinforced ICI’s established global positions and created many opportunities for accelerated growth. Both National Starch and Quest plan to undertake major expansions in China and Asian markets and will benefit from sharing established sites, local knowledge and relationships.

Financing the new strategy

A key component of any strategy involves outlining the major resource decisions required to put the strategy in place. In order to acquire new businesses, ICI has had to sell some of its existing businesses e.g. ICI has sold its polyester polymers and non-US titanium dioxide businesses to DuPont for a staggering £1.8 billion. Between 1997 and the year 2000, ICI is expected to raise over £4 billion by selling its non-core businesses.

ICI has been able to use the funds it has been generating to invest intelligently in areas of the sensory perception market in which it has a competitive advantage. For example, although ICI is world leader in decorative paints, it currently only has 10% of this market. ICI has therefore recently acquired Grow in the USA, Bunge paints in South America and Williams in Europe.

ICI has also looked to bank borrowing to finance its expansion. The acquisition of Unilever’s Speciality Chemicals businesses was financed entirely through a five year bank loan. ICI’s financial director has set a target to reduce dependence on borrowing and to make a return of investment on its new businesses of 20%. Clearly this is a demanding target but is a necessary requirement if ICI is going to transform itself from a less profitable producer of bulk chemicals to a producer of attractive consumer focused products.

Conclusion

Today, ICI is characterised by the production of a range of new products which are used by all consumers. For example, anyone using hair spray is likely to have benefited from its technology because an ICI company holds the licence for the lacquer that holds the product together. Face cream will have a surfactant or emulsifier produced by ICI’s speciality chemicals businesses, high heels will be made of ICI polyurethane, cornflakes will have been made crisper and the packet sealed by ingredients from ICI’s new National Starch business.

It is clear that ICI has come a long way from its original business and provides us with an excellent example of the way in which intelligent organisations are transforming themselves to meet the requirements of the modern consumer.

ICI | The transformation of ICI