The New Deal

Unemployment is one of the worst social evils. It saps the self-confidence and motivation of those it affects directly and has knock-on effects for all members of society. By under-utilising labour, the wealth and economic well-being of the country is reduced. Unemployment can also produce poverty and social exclusion.

Taking policy measures to reduce unemployment should therefore be high on the agenda of any government. Today, unemployment is a European-wide issue with over 18 million unemployed people across the European Union. The seriousness of this issue is recognised and the European Council at Amsterdam has agreed a new employment chapter in the Treaty, Council Conclusions on Employment and a Resolution on Growth and Employment. These set a clear agenda at a European level for action to create jobs and attack social exclusion. The primary responsibility for tackling unemployment, however, remains at member state level.

This case study examines the importance of creating an effective labour market in order to reduce unemployment. In particular, it focuses on a specific government economic measure, the New Deal, as an example of the way in which governments can use policy measures to create a more efficient labour market and increase employability. The New Deal is a labour market initiative which aims to improve an individual’s employment prospects and reduce the incidence of long term unemployment by ensuring a continued attachment to the labour market.

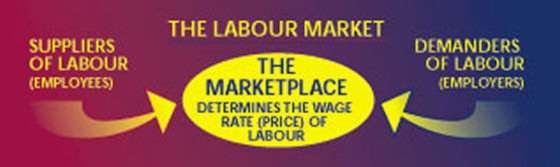

The nature of the labour market

In the labour market employers have to compete with each other for human resources. Workers ‘supply’ some of their time and effort to organisations for a wage while the organisations ‘demand’ labour in order to produce goods and services. The labour market plays a very significant role in resource allocation. The interaction of demand and supply determines the price of labour which is known as the wage rate. Wages are most likely to be high in those industries and jobs where the demand for labour is high and where the supply of labour is relatively limited.

The final price (wage rate) is set at a point where the demand for labour is matched by the supply. Even in perfectly functioning markets, there would still be some unemployment as new and more efficient forms of economic activity displaced old and less efficient ones and as people changed jobs.

Changes in the labour market

The demand for labour is what economists term a derived demand. Generally, employers do not want labour for the sake of hiring labour, rather, they hire employees to make goods and services which are demanded by final consumers. In simple terms, we can say that the demand for labour is derived from the demand for goods and services.

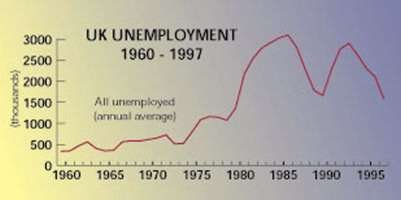

The sale of goods and services is highest when the economy is growing strongly. Therefore, economic growth leads to a higher demand for labour to produce those goods and services and a lower rate of unemployment. The figures for unemployment and economic growth in the UK since the 1960s, confirm that every time economic growth is negative, unemployment rises and does not fall back until the economy starts growing again.

However, after each recession in Europe, unemployment has not returned to pre-recession levels. For instance, as a result of the recession of 1974-75, in the UK, unemployment rose from 2.1to 5.2in 1977. When economic growth recovered, unemployment only fell back to a minimum of 4.6 More recently the UK has shown that this trend can be broken. Unemployment currently continues to fall even though today’s rate of 6.6is lower than the lowest rate attained (7 during the most recent phase of rapid economic growth in the 1980s.

The costs of unemployment

Unemployment has several disadvantages.

- It has an enormous social cost for individuals and communities.

- It leads to a considerable waste of resources. For example, for approximately 20 years prior to the Second World War, unemployment averaged at least 10in this country with idle machines, factories and employees.

- Rises in unemployment lead to falls in consumer spending. A small fall in consumer demand can lead to a much bigger overall change in incomes and spending. This cycle is known as the multiplier.

- Unemployment imposes a financial cost on workers and the government. This is because the unemployed in the UK receive benefits which are financed from taxes. As the term of unemployment increases, people’s work opportunities reduce and they, in turn, reduce their efforts to seek work and can become excluded from the labour market. This can lead to an increase in poverty and inequality.

Why has unemployment increased?

A number of different explanations have been put forward to try and explain the rise in unemployment since the 1970s. Not all of these explanations are valid and no single one fully explains the growth in unemployment.

1. Globalisation

Between the 1950s and the 1990s, there was a massive increase in the movement of capital around the world due to the liberalisation of trade i.e. a reduction in barriers to international trade. Trade has allowed countries to exploit their natural resources and comparative advantages. For instance, the developing world is relatively abundant in low and unskilled labour and so is able to produce labour intensivshifted from low-skilled and manual jobs towards higher-skilled occupations. However, the number of jobs has increased and unemployment has resulted because workers and firms do not adapt quickly enough to the changing demand for labour, goods and services.

2. Technology

The rise in technology has also contributed to changes in the demand for labour. Machines have replaced jobs in some sectors or occupations, but have also generated demand for new services and have led to an increase in the number of jobs and in employment opportunities.

Together, globalisation and technology have contributed to a net growth in employment. They are the driving forces of rising world prosperity, but have produced a decline in the demand for low and unskilled labour. For instance in the UK, the unemployment rate for those with tertiary level education in 1996 was 3.9compared with 13for those who had not completed upper secondary education.

Changes in the demand for labour are likely to continue. This makes it all the more important that the labour force is flexible and adaptable.

Other explanations of rises in European unemployment include:

- Generous benefit regimes: in the 1970s and early 1980s, the administration of benefits was made less strict, reducing the pressure on the unemployed to seek work. For instance, unemployed claimants in the UK were not required to register at a Job Centre to encourage them to find work.

- Growth of trade union power may have permitted employees to demand a higher level of wages relative to the production of each worker. This may have led to a reduction in the demand for labour (however, a number of commentators suggest that this factor has become less significant in the UK during the 1980s and 1990s as the numbers of trade union members has fallen significantly).

- A long period of high unemployment meant that the number of long term unemployed increased and they became increasingly detached from the labour market. Groups particularly affected included the unskilled and semi-skilled manufacturing workers and particularly those over the age of 50.

- Employers usually have to pay taxes and national insurance contributions for their workers – this ranges from £18 for each £100 of wages paid in the UK to £41 in France. This makes paying employees costly and discourages recruitment.

Policy making for employability

Most people would agree that in a modern society, it is essential to help all citizens gain meaningful and useful employment with long-term developmental opportunities. Governments have a key role to play in creating the framework which supports existing market structures and removing any weaknesses or faults in current market arrangements.

Traditionally, the UK has had very few labour market regulations. Nevertheless the market is not working perfectly. The New Deal for the unemployed is a good example of the way in which a government has set about helping to make the market work better. The New Deal aims to match unemployed people to jobs and focuses on the groups of people who suffer unemployment most – young people, the long term unemployed, lone parents and disabled people. The policy package includes provisions for training to be provided to all participants.

The nature of the problem for young people in the labour market

Young people face particular difficulties in the labour market. On entering the labour market, some young people find it difficult to obtain a secure foothold. Their lack of experience and limited skills means that employers can be reluctant to take them on and incur the costs of training them. In January 1997, 18-24 year olds made up a quarter of the claimant unemployed. Young unemployed people usually have a relatively high exit rate (i.e. they find work relatively quickly) but once scarred by long term unemployment, they have difficulties settling down into stable employment. Being young, they have a long period of potential working life ahead of them and therefore the damage of unemployment to their employability represents a greater economic loss to society.

Unveiling the New Deal

In July 1997, the Labour Government unveiled its rationale for a New Deal by emphasising a new approach to welfare reform in this country:

‘In the new economy….,where capital, inventions, even raw materials are mobile, Britain has only one truly national resource: the talent and potential of its people. Yet in Britain today one in five of working age households has no one earning a wage. In place of welfare there should be work… It is time for the welfare state to put opportunity again in people’s hands. First, everyone in need of work should have the opportunity to work. Second, we must ensure work pays. Third, everyone who seeks to advance through employment and education must be given the means to advance. So we will create a new ladder of opportunity that will allow the many, by their own efforts to benefit from opportunities once open only to a few.’

The 1997 budget then (amongst other reforms) went on to announce preliminary ideas for The New Deal and these were expanded in the March 1998 Budget.

The New Deal for young people

There are a number of New Deals aimed at different groups of people disadvantaged in the labour market. In this case study, we will focus on the New Deal for Young People. The New Deal is for those aged 18-24 who have been claiming Jobseeker’s Allowance for six months or more. It started in January 1998 in 12 ‘pathfinder’ areas before going nation-wide in April 1998.

The New Deal sets out to offer young people continuing, high quality support which is sensitive to their individual strengths, weaknesses and needs and is relevant to conditions in their local area.

It provides:

- one-to-one help and individual support from a Personal Adviser

- access to a wide range of specialist help to tackle barriers to employment

- good quality work, education and training.

The New Deal offers structured support in three main ways:

- the Gateway

- New Deal options

- follow-through.

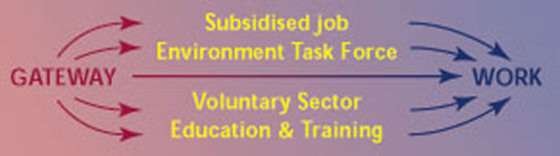

The Gateway

Young people who enter New Deal will begin by spending up to four months in the Gateway.

On entering the Gateway the young person will be allocated a personal adviser who will help and support them throughout their time on New Deal. They will discuss their needs, ambitions and options and agree their New Deal Action Plan.

Many young people will already have good employment prospects, having the necessary skills, abilities and motivation. Intensive careers advice and assistance with finding and applying for jobs should help them move quickly and successfully into employment.

Others may need more help. The personal adviser will have access to a range of local counselling and support services tackling immediate barriers to employment, whether over careers advice, basic skills such as reading or numeracy, or broader issues like homelessness or debt problems.

The four options

For those young people who don’t leave the Gateway for jobs advertised by employers in the normal way, the New Deal offers access to four practical options to help the young person develop the skills and experience necessary to gain and keep a job.

These options are:

- A job with an employer for which the employer will receive a subsidy of £60 a week for six months. Training will always be included.

- Work for six months with a voluntary sector employer. The young person will receive a wage or an allowance equal to their Jobseeker’s Allowance and continue to get any other benefits such as help with rent or council tax, plus a grant of approximately £400 in instalments over 26 weeks. Again, training is an integral part of this option.

- Six month’s work with the Environmental Task Force (with similar rewards to being placed with a voluntary sector employer). The young person will work on a project designed to improve the community’s physical environment and also receive training.

- The option of full time education or training for up to 12 months. This will most likely lead to an NVQ level 2 qualification. A young person will receive an allowance equal to Jobseeker’s Allowance and continue to get any other benefits such as help with rent or council tax.

Follow-through

In order to build on the time, learning and experiences gained, continuing support will be provided during and after the four options where appropriate. The level of support will vary depending on progress and needs and its main objective will be to help individual young people to find and retain employment. The personal adviser will play a key part in providing this support.

Who provides New Deal?

New Deal is being delivered by the Employment Service, national and local companies, local authorities, voluntary organisations, education and training providers (including TECs and LECs) who work together to provide opportunities in their local area.

Monitoring the success of New Deal

It is too early to assess the success of these ambitious programmes but the government is aware of a few possible problems which it aims to limit. The programmes may involve spending money on people who would have found jobs on their own anyway. In economic jargon, this is a dead weight loss which represents a waste of government resources.

In addition, new workers may merely displace existing workers already in jobs, instead of new jobs being created.

Finally, the subsidised jobs for youths and the long term unemployed may distort competition in the market and give some firms an unfair advantage over others. This may lead to some firms being able to sell their products much cheaper than their competitors – possibly driving them out of business.

The success of the New Deal will be judged by whether those helped are more employable and better able to obtain and retain jobs in a continually changing labour market. By increasing the size of the effective labour force, the New Deal will, if successful, enhance the trend rate of growth of the economy i.e. the rate of growth which can be sustained without inflationary pressures building up or inflation emerging.

The immediate effects of the New Deal can be judged by comparing the flows into and out of unemployment each year against pre-New Deal or ‘normal’ flows, adjusting for changing economic conditions. The effect of the New Deal should be to ensure that more people leave unemployment than would have done so otherwise and that the employability of young people is increased. By adding to the effective labour force, it will, if successful, enhance the capacity of the economy to grow without inflation and so enable the Bank of England to maintain interest rates at their current level or to lower them. This in turn will help generate additional economic activity and more jobs. Government officials will evaluate the scheme regularly to ensure that it is meeting its long term aim of increasing overall employment levels in the economy.