This case study examines the importance of futures trading and focuses more specifically on commodity futures trading. The futures market plays a key role in the modern economic system because it enables investors to trade in a cost efficient way and to eliminate some of the risk from their trading activity.

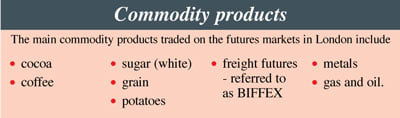

Commodities lie at the heart of modern industrial society and include a wide range of primary products ranging from foodstuffs, such as rice, grain and coffee, to industrial raw materials, such as oil and iron ore. Commodities are subject to price fluctuations over time – due to changing supply and demand conditions in the market place.

Demand and buying patterns can change – for example, more oil than normal may be consumed during a particularly cold winter and so demand increases. The commodity supply chain can also vary considerably for a variety of reasons – frosts may destroy olive trees in Southern Italy, potato blight may wipe out a crop in the East of England, political upheavals in the Middle East may prevent the free flow of oil.

There is an element of risk in any activity when the outcome cannot be predicted with certainty, or when the outcome is known but its full consequences are not. Individuals have widely different attitudes towards taking risks. It is possible to identify three different positions:

- The risk lover – someone who enjoys a gamble, even when mathematical analysis shows that the odds are unfavourable.

- The risk-neutral person – will only speculate if the odds on a gain are favourable. The person will not be concerned with the range of possible outcomes, only with the odds being in their favour.

- The risk-averse person – will not leave anything to chance and only speculates if the odds are strongly favourable.

In business, organisations also take risks. Some are prepared to take large risks which can make or break the organisation but more typically, organisations aim to manage their risks.

For example, organisations which require large quantities of a certain commodity (Burger King needs vast quantities of potato chips, Nestlé requires coffee beans etc.) will seek to take advantage of the futures market by fixing their future price for buying potatoes, coffee beans and aluminium etc. In a similar way, organisations exposed to interest rate movements or price changes on the Stock Exchange will benefit from using the futures market.

Commodity futures markets allow traders, manufacturers and end-users to hedge against future price fluctuations. Trading is traditionally carried out by the method known as ‘open-outcry’. Traders face each other in the trading ‘ring’ or ‘pit’ (referred to as a trading ‘ping’, i.e. a mixture of a ring and a pit) and shout their bids and offers. This means that everyone is completely aware of available business opportunities. Once a deal is struck, the tonnage and price are made public via computer links and through the financial and trade press. Advances in computer technology mean that it is possible to trade futures via electronic trading systems as well as open-outcry. Instant information technology connections mean that futures trading can take place via terminals on office desks and not just through local trading centres.

The futures industry

Initially, the Chicago exchanges concentrated on grain contracts before expanding into cattle, pig meat, soya, lumber and other agriculture-related commodities. The London exchanges originally concentrated on metals and soft commodities but have developed, over the years, to deal with a much wider range of commodities. However, in the last 25 years, there has been rapid growth in financial futures and options trading globally, covering mainly interest rate, bond and equity related products.

Since 1982, the London International Financial Futures and Option Exchange (LIFFE) has provided a market place devoted to serving the demanding and ever changing needs of the world’s financial community. LIFFE is the second largest futures and options exchange in the world and the largest in Europe. Since September 1996, it has traded agricultural and soft commodity products. The success of the Exchange has reinforced the City of London’s strategic position as a centre of international finance.

How LIFFE works – an overview of open-outcry

A client wishing to buy or sell futures or options telephones their broker who is a member of LIFFE. The broker contacts their booth on the LIFFE trading floor with the client’s instruction. The order is received in the booth, written onto a ‘client order slip’ and then stamped with the time when the order was received. The pit trader is given the information either by hand signals or by a written order from the booth clerk. It is then offered to other traders in the pit.

The first trader to respond by calling, for example, ‘Buy 100’ or ‘Sell 100’, becomes the counterparty to the deal. Once executed, the order slip is time stamped again to show the exact time the trade took place. The broker then informs his client that his order is filled. Both parties then input the trade details into the matching system. Matched trades are passed to the London Clearing House which acts as a central counterparty.

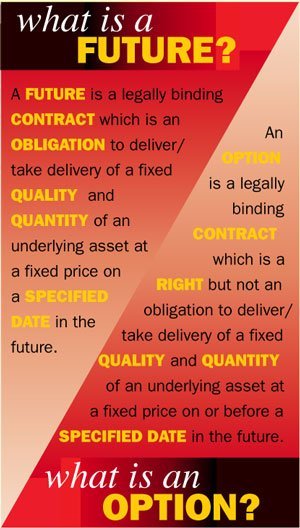

There are two kinds of options – calls and puts. The buyer of a LIFFE commodity call option acquires the right, but not the obligation, to buy a futures contract at a predetermined price on a given date. The buyer of a Liffe commodity put option acquires the right, but not the obligation, to sell a futures contract at a predetermined price on a given date. Call and put options can be bought and sold.

In each case, the seller of an option earns the premium, which is the agreed price of the option, but may be called upon to sell (call option) or buy (put option) a futures contract should the buyer exercise the right to buy (call option) or sell (put option) a futures contract

- hedging

- speculation

- arbitrage.

Hedging accounts for the majority of traded volume, followed closely by speculation, whilst arbitrage accounts for only a small percentage of trading activity.

Hedging

Most large organisations buying particular commodities know that they will need a regular supply of the products over a long period of time. These organisations may need to replenish supplies on a regular basis with cover for three, six or nine months. Of course, in three, six or nine months time, the price of that commodity may have substantially increased due to, for example, a harvest failure or a natural disaster in a key supplier country. In order to take some of the risk out of future purchases, it is possible to hedge.

Hedging involves matching the sale or purchase of commodities with an opposite transaction (i.e. the purchase or sale of a similar quantity of the same product) on the futures market. Here is a very simple example:

A company contracts to sell potatoes in six months time at the current spot price, being the price currently obtainable. However, the company is concerned that when the time comes to honour the contract, the price of potatoes will have risen. As a result, the company will lose money, either because it could have sold its potatoes at the higher price or because it will itself have to buy potatoes at the higher price to honour its contract. To protect itself against that possible loss, the company contracts to buy a similar amount of potatoes at the price that the market thinks will be obtainable in six months time (in other words, it buys a six months ‘future’ in potatoes). So, whether the price of potatoes rises or falls, the company will not lose money (nor, of course, will it make money if the price rises – other than the profit built into the original contract).

‘Perfect hedging’ assumes that the futures price is the same as the future ‘spot price’. Usually there is a slight variation but occasionally, due to some unforeseeable event, the variation can be considerable. Hedging of course is only possible because many dealers (particularly speculators) are willing to take an ‘uncovered’ risk, agreeing to a contract without themselves setting up an identical and opposite contract.

Most commodity futures contracts take the cost of warehousing, transporting and financing a product into account and therefore will have a slightly higher price than a product purchased on the spot market. Oil, for example, may have a price of $20 per barrel on spot but may cost, say, $20.50 traded on a future to accommodate the above differences.

Speculators

Speculators are a key feature of many modern markets. Speculators try to make a profit by predicting future changes in prices. Speculators play a major part in international currency and financial futures markets as well as in commodity trading. A speculator is not concerned with the physical delivery of anything – they would not want 10,000 tonnes of potatoes! Instead, the speculator is more concerned about buying / selling on the contracts that they make in international exchanges at a considerable gain. A speculator fits into the category of the ‘risk lover’. They seek to make a quick profit through successful futures transactions.

Arbitrage

The third type of activity carried out in the futures market is called arbitrage. It involves the simultaneous purchase of an instrument in one market against the sale of the same or similar commodity in another market to exploit pricing differentials.

LIFFE ensures that the commodities being traded are tightly monitored and controlled. LIFFE has approved a number of authorised warehouses and warehouse keepers who are responsible for the careful handling and storage of commodities, for their organised sampling, as well as the maintenance of accurate and scrupulous records. For example, cocoa and coffee are graded and sampled by suitably qualified persons appointed by LIFFE. All grain delivered against wheat and barley futures contracts must be segregated from all other grain and kept in a LIFFE registered grain store.

Clearing and settlement

LCH takes security from members to protect against another member being unable to pay its losses. There are two elements to this margin:

- Variation margin – these are profits or losses on open positions which are calculated daily in the marking to market process and then paid to or collected from members.

- Initial margin – this is a returnable deposit required by LCH when opening futures and options positions.

Take coffee as an example

Coffee is an important commodity, with over 50 producing countries and 25 million people employed in coffee trade world-wide. It takes four years before a newly planted coffee tree can provide a reasonable harvest. There are many different types and grades of coffee and the taste or ‘cup’ is affected by the method of growth/processing.

Coffee is prone to disease, insect and weather-related catastrophes and therefore shows major fluctuations in price. For example, in 1994, there were two major frosts and a drought in Brazil which affected the amount of coffee produced and, therefore, the final price.

The futures market enables these businesses to work in an ordered and disciplined market place in which the risk of rapidly changing commodity prices is greatly reduced. It reduces the risk of uncertainty from uncontrollable events, such as a bad coffee harvest, enabling traders to buy and sell commodities in the future, at prices specified today.