Most companies that manufacture or use packaging accept that they need to produce and use it in ways that are environmentally, economically and socially responsible. This case study outlines the nature of that challenge and shows how the packaging industry has itself created a body that works to encourage responsible attitudes towards packaging in modern society.

History

In the 1970s the packaging industry faced a number of issues. The two oil crises of 1973 and 1978 produced a situation from which energy conservation became a top priority. Some companies appointed senior managers with the sole task of overseeing and controlling energy. Goods manufacturers and retailers were demanding ever lighter packs that would cut the amount of resources used in manufacture and the energy used in transportation. Environmental groups were using packaging in their campaigns as a symbol of the ‘throwaway’ society.

By the affluent 1980’s, the emphasis was shifting. What had been a serious energy problem had been replaced by what was seen as a solid waste dis-posal problem. People were less worried about the energy being used and more concerned about what happened to the waste. Environmental groups argued that packaging should be reduced to help solve the ‘waste problem’.

Challenges

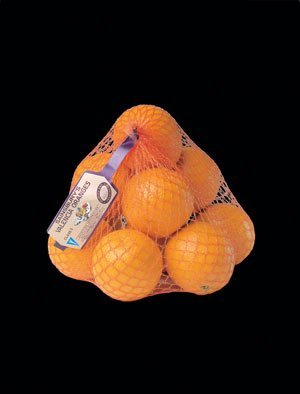

For economic reasons, companies design packaging to use just enough, and no more, material than is needed to ensure that goods survive the distribution chain and are delivered to consumers in good condition. In developing countries, up to 50% of food is wasted on the journey from farm to shop. In Western Europe, less than 3% goes to waste. However, companies are also faced with the problem that consumers often say that they think packaging is a waste of resources. This is not really surprising because people go shopping for low-calorie lasagne, baked beans or fizzy orange juice and tend not to notice the carton, can or bottle until they have eaten or used the contents and the packaging becomes ‘waste’.

Packaging’s various roles – ensuring that goods survive the hazardous journey through the distribution chain and enabling efficient handling of goods, which in turn helps keep costs to consumers down – are usually taken for granted. Packaging is a significant fraction – between 20% and 25% by weight – of municipal solid waste, which is largely household waste. What the consumer does not see is that household dustbin waste makes up less than 20% of the total solid waste from all sources sent to landfill in a typical European country. Landfill is dominated by industrial, demolition and construction waste. Household packaging accounts for less than 5% by weight or volume.

Formation and role of INCPEN

Rather than respond to these issues individually, companies in the packaging sector decided to set up a joint body,The Industry Council for Packaging and the Environment (INCPEN) to carry out research into the environmental and social effects of packaging. INCPEN produced the first detailed estimates of the amount of packaging that enters the waste stream and its relationship to total waste generation. It has commissioned studies into the energy requirements of packaging production and packaging distribution systems, and it has carried out surveys of litter.

INCPEN commissioned an independent study on “Packaging in a Market Economy” which examined the functional, environmental, social and economic considerations involved in packaging assessment, including case studies on the packaging for fish, computer monitors, liquid detergents and luxury cosmetics (see https://www.incpen.org/html/workingp.htm). More recently, it has published a report on the environmental impact of packaging in the UK food supply system, investigating the resource requirements of food packaging against those of food production and distribution.

The findings from this research have been used to promote good packaging practices and to inform legislators, consumers and interest groups about the role of packaging. One of the reasons for setting up a joint body is because there is not a ‘packaging industry’ as such. All companies in the goods supply chain have some influence on packaging including:

- raw material manufacturers e.g. steel manufacturers

- packaging manufacturers e.g. can, bottle and wrapping manufacturers

- manufacturers of packaged goods

- retailers of goods.

Packaging is a ‘product’ for a can manufacturer. For a baked beans manufacturer, however, it is part of the system for delivering the beans to the consumer. It performs a range of functions.

The environmental impact of packaging

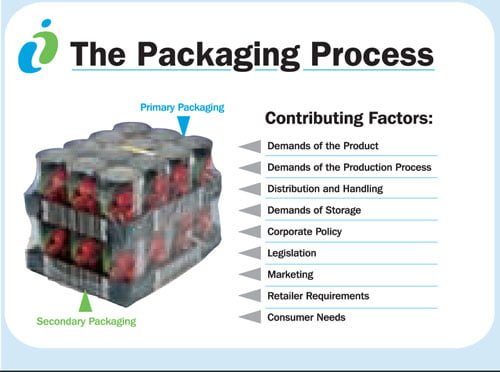

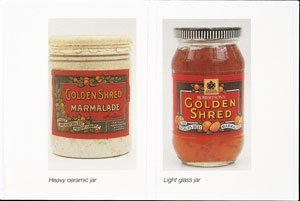

Choice of packaging type is made on the basis of a series of trade-offs between many factors, particularly between the amount of packaging and likely product wastage. Manufacturers of goods look for a balance between:

- protecting their goods (the cost of damaged goods or the danger from spoilt foods is far worse for the environment than using a small amount of extra resources to make a stronger pack)

- protecting public health

- protecting the environment

- protecting themselves (by complying with legal demands on health and safety standards)

- protecting their business by keeping their products competitively priced

- providing what the consumer needs (easy opening packaging for the elderly, smaller portions for individuals who live alone, tamper evidence etc.)

- providing presentation and branding

- providing information about the goods.

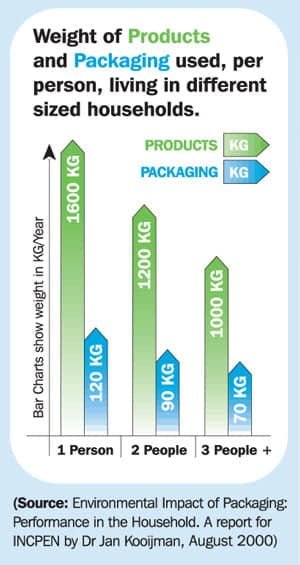

Since 1961 the UK population has grown by 11% from 55 million to 60 million. In the same period, the number of households has grown much faster, by almost 50%. This has meant that the average household size has dropped from 3.1 to 2.3 inhabitants with a consequent huge increase in environmental impact. No matter how many inhabitants it has, each household needs hot water and heating. Most households now have a cooker, fridge, washing machine and a host of other appliances and gadgets.

Cooking food has a much greater impact in smaller households. It takes almost the same amount of energy to boil one egg as it does to boil four at the same time. Large households are relatively efficient in terms of food. They buy larger sizes, eat more meals together and therefore per person they generate far less waste. A person living alone has roughly double the environmental impact of one who lives in a large household. Some requirements, particularly the demand for smaller-sized portions, means that the demand for packaging will grow rather than decline.

At the same time there are compensating developments that will tend towards reduced packaging. For example, many companies, especially in the retail sector, are increasingly designing all the packaging needed to protect goods (the packaging immediately containing the goods, the secondary or grouping. Packaging and the packaging used to transport the grouped packs) as complete systems. This has made more effective use of resources. Consumers are increasingly willing to buy concentrated products in lightweight refill packs for dilution at home. Companies are increasingly informing consumers about the choices available to them, enabling them to make informed decisions about the products they buy and how to use them efficiently.

In the 1970s there was an informal agreement between packaging chain companies in Europe that they would not use environmental issues as a marketing tool for competitive advantage, nor make environmental statements that might confuse consumers. The companies that formed INCPEN as a voluntary initiative operated at all stages in the supply chain. Today, INCPEN’s 60 members are major international companies from all parts of the chain. This cross-sectoral membership provides a unique “pool” of research facilities and knowledge and enables INCPEN to effectively represent its members’ views from a strong but impartial position.

Managing waste

The concentration on packaging as waste has led to two separate issues being confused:

- the need to design good packaging systems that get products from manufacture to consumption with the minimum necessary expenditure of resources

- the need to invest in modern solid waste management techniques so that we can reduce the environmental impact of ALL waste, not just packaging.

This confusion has two unfortunate consequences:

- it gives a false impression that all one has to do to solve the waste problem is to remove packaging from waste

- it over emphasises one environmental consideration – waste – and distracts attention from designing resource-efficient packaging that can make the best use of all resources throughout the distribution chain.

INCPEN’s work

INCPEN’s early work led to the publication of a number of discussion papers that influenced the Government’s approach to policy on packaging and encouraged innovation. Today there is less packaging per capita put on the market in the UK than in any other major European country. (Source: Member States returns to European Commission re: the Packaging and Packaging Waste Directive)

INCPEN also works with consumer and environmental groups to explain the role of packaging. INCPEN coordinates a network of over 40 trade associations, representing more than 85% of companies in the packaging chain. These associations commend to their members the use of INCPEN’s Responsible Packaging Code of Practice to demonstrate commitment to responsible packaging in the context of sustainable development. The Code aims to improve packaging and minimise waste. INCPEN’s research is acclaimed internationally for its impartial assessment of environmental issues.

How legislation can restrict trade

In 1991, Germany introduced a law that set a quota for the percentage amount of drinks that were allowed to be sold in non-refillable containers. This law requires that at least 72% of drinks have to be in refillable bottles. Other European countries argued that this was a barrier to trade, on the basis that, if their drinks had to be packed in refillable containers (which are inevitably heavier than non-refillables), they would incur higher transport costs. This would then result in their drinks costing more than those produced locally. Free trade is the key under-lying principle of the European Union.

INCPEN lodged the first formal complaint against the law in June 1991. It explained that the legislation not only discriminated unfairly against imports to Germany, but more importantly, that it did not produce any environmental benefit. Refillable containers are often not the best choice environmentally, socially or economically. They sometimes generate less waste but they always use more energy in production and transport.

In 1994 the European Union passed a Directive aimed at removing such obstacles to trade. It also aimed to encourage reduction of the environmental impact of packaging. This is known as the Packaging and Packaging Waste Directive. Seven years later, the German refill quota is still operating and other countries have enacted or proposed similar protectionist measures. However, the European Commission decided in early 2001 to refer the German law to the European Court of Justice. Unfortunately for many companies, the case will relate only to mineral water, which is required by other European laws to be bottled where it arises.

Conclusion

Today, INCPEN’s major challenge is to develop effective working partnerships with the regulators to ensure that policy on packaging aligns more closely with the major challenges of sustainable development, rather than simply seeking to reduce the quantities of packaging materials used.

Current restrictive laws on packaging need to be replaced with policies that enable companies to develop packaging systems that will help make more efficient use of resources in getting goods from point of production to consumption. In other words, INCPEN’s aim is to line up packaging policy with the main environmental objectives of reducing emission of global climate change gases and encouraging sustainable development. The packaging chain is dynamic and deserving of further study.