After the Second World War, the British welfare state was further strengthened. The welfare programme offered citizens an education, an opportunity to find a job, adequate housing, free healthcare and financial support in times of special need. The state guaranteed a certain minimum level of provision that did not depend on people’s ability to pay. If people wanted something better, then they were free to find it and pay for it.

Fifty years on, most British politicians remain committed to the idea of a welfare state that includes free education, a National Health Service, and selective financial support. They recognise, however, that people’s needs have changed, along with their expectations of what governments can and should be reasonably expected to provide. For example, people now look to have greater control over their own lives and over the social and economic choices they make. Many citizens are clearer about their own rights, particularly as consumers, whilst governments regularly remind them of their responsibilities as citizens.

Faced with increasing demands on what the welfare state provides, governments have also reviewed how best they can identify and help those in greatest need. In looking to provide a more efficient welfare state, in which services and benefits are better targeted on those who most need them, the present UK government is also seeking to protect the interests of those citizens who, as taxpayers, pay for the welfare system. So the welfare state is being rethought, reformed and modernised.

The DfEE (Department for Education and Employment) is responsible for improving two main areas: education and opportunities for employment. The DfEE recognises the link between the quality of education that young people receive and their chances of finding a job. It is acting to improve young people’s education. At the same time, the DfEE is looking to improve how the labour market works, so that the number of people able to find jobs is markedly increased at every stage of the business cycle.

This case study outlines the DfEE’s action programme for employment. The programme’s main aim is to reduce the number of people dependent on welfare benefits because they have no job and to help them move ‘from welfare into work’.

Unemployment and the economy

Economies change over time. Firms come and go, industries rise and fall, new jobs are created, old ones disappear. Some areas flourish, others decay. Throughout all this, people try to stay in work. Many succeed, but some don’t. The challenge to them and to the government is to find them another job before they lose heart, stop searching, and are lost from the labour force.

Over the past twenty years, successive governments have looked to improve the way the labour market works. For people to obtain jobs, they must know that a vacancy exists. They also need the education and training that the vacancy requires, so governments have looked to improve job advertising and job training.

That is not enough, however. People need to feel motivated about taking a job. Being employed has to be made to look attractive and rewarding. Guaranteeing a minimum wage has a part to play, but so does reform of the tax and social security system, so that people keep more of the money they receive as a result of being employed rather than unemployed.

Unemployment has been falling steadily since December 1992. The proportion of people of working age who actively seek work is tending to increase, so if unemployment is not to rise, the number of jobs available has to increase. Over the past ten years, the UK economy has continued to grow, new jobs have been created, and the number of people with a job is currently at a record high. This is a significant achievement and a major contributor to citizens’ welfare. Some problems remain, however:

- There are pockets of low employment and high welfare dependency in some, mainly urban areas.

- The number of households in which nobody has a job has, until recently, tended to rise.

- Opportunities for young people to find work vary widely from place to place.

These trends suggest that the benefits of a growing economy are not being evenly distributed. A significant group of people and households are ‘missing out’ on the job opportunities and higher prosperity that an expanding economy has brought to many others. Their plight is a serious challenge for policy makers.

Creating an action plan

All EU countries produce an Employment Action Plan. Its key themes focus on ‘Work for those who can, security for those who can’t’ by:

- raising employment across the EU

- social inclusion

- opportunities for all.

The Action Plan’s main aim is to help all people to find work, particularly for those where a long period of being without a job has left them feeling detached from the world of work and cut off from the rest of society. At the same time the Plan helps them to acquire skills that will be attractive to employers.

The government intends to implement the Action Plan through its own departments but also in partnership with other bodies. These include:

- the Scottish Executive and the National Assembly for Wales

- the newly created Regional Development Agencies (RDAs)

- the Equal Opportunities Commission and the Commission for Racial Equality

- local authorities, trade unions and other representative bodies.

The modernised welfare state

The government believes that the best form of welfare for people of working age is to provide them with help to find work. This should raise not only their income but also their self-esteem, which in turn contributes to their health and well-being.

The government’s employment policy is built around four key ideas:

Employability – Helping people to find and keep a job involves:

- providing them with better education and training

- giving advice and support to anyone looking to move away from dependency on benefits and into a job, through a Welfare to Work programme

- improving the attractiveness of work through a minimum national wage and changes to the tax and benefits system in favour of people in work

- encouraging firms to improve their ongoing training programmes

- promoting a culture of lifelong learning so that people remain employable.

Entrepreneurship – This involves encouraging employers to be more innovative, more enterprising, more forward thinking so that UK firms remain competitive in world markets.

Adaptability – This includes helping businesses to become more willing and able to change and encouraging employees to respond positively to change.

Equal opportunities – This involves:

- providing women with the same career and promotion opportunities as men

- providing people from different ethnic groups with the same chance of a job

- guaranteeing people of different ages the same chance to find and retain a job

- offering people with disabilities the same job opportunities as able-bodied persons.

- overcoming discrimination in the workplace, through a mixture of education, persuasion and legislation.

You can do it. We can help

For people wanting to avoid dropping out of the labour market, some times are more risky than others e.g. leaving school, moving areas, being made redundant. The government’s policy is to provide extra support at such times. This support includes:

- Educational maintenance allowances (EMAs) – These encourage 16 and 17 year olds who leave school to continue in further education, thereby improving their employability.

- Jobcentres – A national network provides easy access to information on unfilled vacancies and to advice, counselling and more in-depth help for those who need it.

- Jobseeker’s Allowance (JSA) and Employment Service – The allowance enables unemployed people to continue their search for a job. With the right to an allowance goes the responsibility to look for a suitable job with the help of the Employment Service.

- New Deal programmes- Of the several New Deal programmes, two are aimed at people receiving unemployment benefits. One is for young people aged 18 – 24 who have experienced long term unemployment (at least six months), who no longer feel part of the work scene and whom employers tend to view as unemployable. The other programme is for people aged 25 and over who have been long term unemployed, for two years.

The New Deal for young people offers individually focused help to find work and improve employability for all young people aged 18-24 who have claimed the Jobseekers Allowance for six months or more. The New Deal for people aged 25+ offers help to those over 25 claiming JSA for two years. It is being extended and enhanced from April 2001.

For the over-25s, the most vulnerable are people who face additional obstacles. These include lone parents, disabled people and people aged 50. A number of additional New Deals help support these client groups. The government knows that even the best policies and help packages will not work if people are reluctant to visit the people and places where they can obtain help. The contact points, e.g. Jobcentres, are being upgraded to make them more user-friendly.

Conclusion

Does all this make a difference?

The new initiatives appear to be working. Unemployment continues to fall, and the number of people in work continues to increase. Independent evidence from NIESR shows that the net impact of New Deal is that unemployment is lower and employment is higher, and because of the impact of welfare spending and tax receipts, the New Deal has been close to self financing in its first two years.

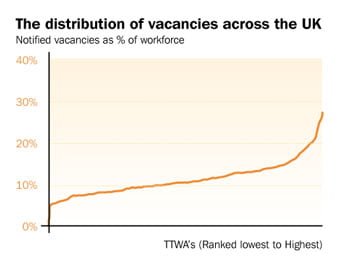

One main aim of recent policy has been to make people’s chances of finding a job less dependent on where they happen to live. Job opportunity is measured in two main ways: the number of applicants for each advertised vacancy and the number of notified job vacancies as a percentage of the local workforce.

Graph 1 shows how the number of job vacancies, as a percentage of the local workforce, varies in different parts of the UK. It suggests that most people have a good chance of finding a job wherever they live. At the extremes, wide variations remain, but for about seven eighths of the UK workforce the ratio lies between 7% and 15%. This suggests that, other things being equal, for most people their chance of finding a job is likely to be at least half as good as that of someone living anywhere else in the UK. This data relates only to job vacancies notified to Jobcentres.

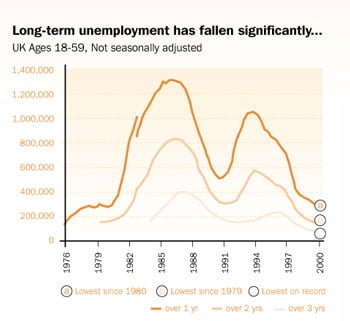

Graph 2 illustrates the success of recent measures in reducing the number of people unemployed for a long time. Notice that the overall pattern is cyclical. By 1994, in response to a slowdown in the economy, the total number of long term unemployed had risen dramatically to around 1.8 million. By the year 2000, this figure is down to just 300,000.

The labour market is doing better at creating jobs and fitting people into them. This has helped achieve another success. The UK economy is experiencing sustained economic growth without inflation. Another key economic objective has been met.

Welfare to work (PDF)

Welfare to work (PDF)