Today, a jar of instant coffee can be found in 93 per cent of British homes and increasingly consumers are trying out different types of coffee, such as cappuccino, espresso, mocha and latte. The expanding consumer demand for product choice, quality and value has led to an increase in the coffees being made available to a discerning public. ‘value’ is the way in which the consumer views an organisation’s product in comparison with competitive offerings. So how does coffee get from growing on a tree perhaps 1,000m up a mountainside in Africa, Asia, Central or South America, to a cup of Nescafe in your home, and in millions of homes throughout the world?

This case study explains why Nestlé needs a first class supply chain, with high quality linkages from where the coffee is grown in the field, to the way in which it reaches the consumer.

The Supply Chain

The supply chain is the sequence of activities and processes required to bring a product from its raw state to the finished goods sold to the consumer. For coffee, the chain is often complex, and varies in different countries but typically includes:

- Growers – usually working on a very small plot of land of just one or two hectares. Many do some primary processing (drying or hulling) themselves

- Intermediaries – intermediaries may be involved in many aspects of the supply chain. They may buy coffee at any stage between coffee cherries and green beans, they may do some of the primary processing, or they may collect together sufficient quantities of coffee from many individual farmers to transport or sell to a processor, another intermediary, or to a dealer. There may be as many as five intermediary links in the chain

- Processors – individual farmers who have the equipment to process coffee, a separate processor, or a farmer, co-operative that pools resources to buy the equipment

- Government agencies – in some countries the government controls the coffee trade, perhaps by buying the coffee from processors at a fixed price and selling it in auctions for export

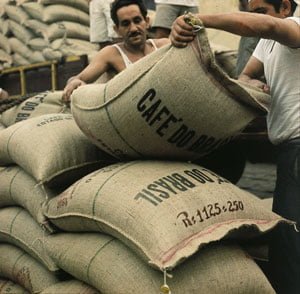

- Exporters – they buy from co-operatives or auctions and then sell to dealers. Their expert knowledge of the local area and producers generally enables them to guarantee the quality of the shipment

- Dealers/brokers – supply the coffee beans to the roasters in the right quantities, at the right time, at a price acceptable to buyer and seller

- Roasters – people like Nestlé whose expertise is to turn green coffee beans into products people enjoy drinking. The company also adds value to the product through marketing, branding and packaging activities

- Retailers – sellers of coffee products which range from large supermarkets to hotel and catering organisations, to small independent retailers.

A supply chain is only as strong as its links. Different relationships exist between organisations involved in the separate stages of the chain – whether it is in the structuring of product distribution, arrangements for payment and arrangements for handling, or in storing the product. At the heart of these relationships is the way in which people treat each other. Long-term business relationships need to be based on honesty and fairness – parties to a trading agreement need to feel that they are getting a fair deal.

Growing and Processing coffee

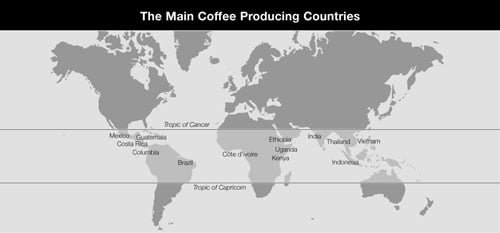

Coffee grows best in a warm, humid climate with a relatively stable temperature of about 27°C all year round. The world’s coffee plantations are therefore found in the so-called coffee-belt that straddles the equator between the tropics of Cancer and Capricorn.

Processing

Coffee from the tree goes through a series of processes to end up with a saleable product – the green coffee bean.

1. Picking – Coffee is picked by hand. Coffee cherries are bright red when they are ripe, but unfortunately, the cherries do not all ripen at the same time. Picking just the red cherries at harvest time produces better quality coffee, but it is more labour intensive as each tree must be visited several times during the harvest season. Many farmers, therefore, strip the tree of both ripe and unripe cherries in one pick.

2. Drying and hulling – The cherries each contain two beans which have to be separated from the surrounding layers – the skin, the pulp and ‘parchment’ – by hulling. The beans also have to be dried, usually in the sun but sometimes by using mechanical dryers.

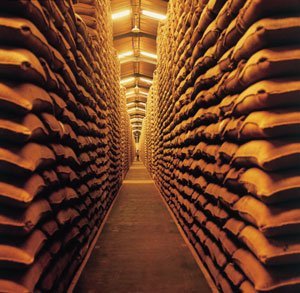

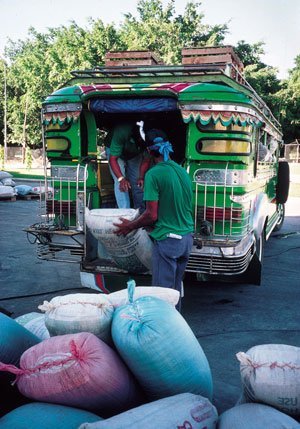

3. Sorting, grading and packing – Beans are sorted by hand, sieves and machines to remove stones and other foreign matter, to remove damaged or broken beans, and to sort beans into different qualities or ‘grades’. Coffee is packed into sacks, usually 60kg.

4. Bulking – Roasters, like Nestlé, will need to buy large quantities of coffee of a particular grade, so exporters in the country of origin will bulk together numerous small batches of coffee to make up the necessary amount of the required grade.

5. Blending – At the roasters, experts with fine palates and much experience decide which blend of coffees from various origins to use to make the coffee products to meet the taste of their consumers.

6. Roasting – On leaving the plantation, the coffee is pale green – hence the name ‘green coffee’ for the traded product. Only when it is roasted does it turn brown taking on its characteristic aroma and flavour. It is the roasted beans which are used to make the coffee product.

Price – Balancing Supply And Demand

Coffee prices are determined day-to-day on the world commodity markets in London and New York and with so many intermediaries standing between the producer and the consumer, how can we ensure that coffee growers receive a fair reward for their labours? Is the answer – as some believe – for coffee manufacturers to cut out the intermediaries, buy their coffee direct from farmers and guarantee a minimum price? The price of coffee is determined by the relationship between the amount of coffee available to be sold (supply) and the amount which people want to buy (demand). If there is more coffee available than people want to buy at current prices, the price will fall. The market thus ultimately determines the price that the farmer receives.

There are circumstances in which farmers can receive more than the market price, for example:

- If the quality of their coffee is high

- If they undertake some or all of the processing stages that someone else would otherwise be paid to do

- If they can sell direct to a manufacturer rather than to intermediaries.

Farmers can also reduce their costs if they are able to share processing and transportation facilities with other farmers. Coffee farmers may sell their coffee in a number of ways

- They can sell to the next link in the traditional supply chain – the collector or processor

- They may sell to government agencies in countries where the coffee trade is government controlled, although this is becoming less common or, they might sell directly to a manufacturer like nestlé.

However, farmers usually cannot choose the method by which they sell their coffee. Selling directly to manufacturers is attractive as farmers potentially receive above the market price. However, it would be impossible for all the world’s coffee to be bought directly by manufacturers from individual farmers a few bags at a time. Although direct purchasing is attractive, it is only one of a number of methods of trading, all of which have their merits and none of which is necessarily fairer than the others. Ultimately it is the market price which determines how much farmers receive.

Nestle´s Trading Methods

Nestlé is a pioneer in purchasing coffee directly from growers. A growing percentage of the company’s coffee is bought directly from the producer and it is now one of the world’s largest direct purchasers. In countries where this is not possible, Nestlé operates in a way that takes it as close to the growers as possible.

Buying Direct

In coffee-growing countries where Nestlé also manufactures for export or local consumption, it has a policy of buying coffee direct from the farmers. The company offers a fair price to the farmers, and so ensures regular supplies of guaranteed quality for its own factories. Higher quality commands a higher price – a premium that Nestlé is happy to pay since good quality raw materials are essential to its business. In countries where direct buying takes place, there is a widely advertised Nestlé price and a minimum base price. By providing a reference level for growers, other traders are forced to keep their offer prices competitive.

Nestlé began its direct buying policy in 1986 and the amounts involved have steadily increased. In 1998, around 15 per cent of its green coffee purchases were bought directly. As an example, in the Philippines, farmers bring their produce to Nestlé’s buying centres situated in the coffee growing regions. Quality is analysed while they wait and growers are paid on the spot. In 1998, direct purchases accounted for over 90 per cent of the green coffee destined for its two instant coffee factories in the country.

Buying From Dealers

In countries like the UK, it is simply impossible for companies like Nestlé to buy from the hundreds of thousands of farmers who ultimately supply the company, so the coffee is bought from dealers using the international market. However, Nestlé visits and gets to know as many people as possible in the supply chain. The company oversees the relationship between the dealer and exporter and often invites shippers to the UK to train alongside its own quality assurance staff. Nestlé agrees with procedures on everything from pest control to methods of packing to ensure everyone is working towards the highest standards of quality.

Conclusion

Creating wonderful cups of coffee is not only Nestlé’s business, it is the business of everyone involved in the supply chain. It is in everyone’s interest – the farmers’ and Nestlé’s – that farmers receive a fair income from their coffee. This ensures that they will continue to grow coffee and to invest in increasing their yield and quality, and this in turn guarantees the supply of quality coffee which companies like Nestlé require.