- primary – gifts of nature such as extracting or developing natural resources including farming, forestry, mining or fishing

- secondary – manufacturing and the construction industries or the making of goods on a large scale

- tertiary – service industries which are made up of either commercial services concerned with trading activity or direct services to people such as teachers or doctors.

Structural change refers to a shift in the importance of these sectors to the economy as a whole. As people in societies have an increasing amount of disposable income, so demand patterns change, resulting in a greater demand for luxury goods. This is illustrated by the current boom in the UK for computer services and financial services, together with recreation and entertainment.

Modern industrial societies such as the UK and the United States have been termed ‘third wave’ societies:

- ‘first wave’ – agricultural based society

- ‘second wave’ – the domination of manufacture

- ‘third wave’ – a switch to service occupations.

As manufacturing has developed and become more complex – for example, by providing higher levels of support services – then jobs that might previously have been termed as manufacturing now fall within the services sector. This concept is referred to as ‘outsourcing’. Manufacturing is an important part of the UK economy. It employs four million people, indirectly supports a further 4.5 million and generates 20 per cent of the Gross Domestic Product.

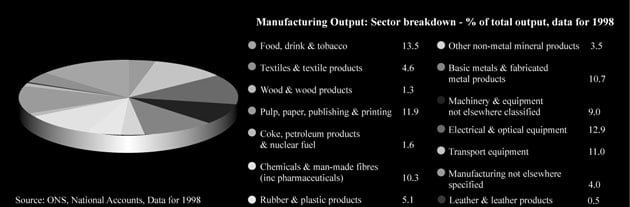

The Gross Domestic Product is the output of goods and services produced by factors of production owned within the UK. Manufacturing is split into a number of sectors. Manufacturing generates new technologies that perform a vital role in aiding the performance of other parts of the economy.

However, manufacturing industries field the full brunt of global competition, with manufacturing production ten times more likely to be traded across international boundaries than services. The industry has to embrace change that, with help, enables it to raise efficiency to compete against best practice within global markets.

This case study focuses upon how the CBI, through the establishment of the National Manufacturing Council, works with manufacturing companies to help them to raise performance levels.

The CBI, is a national organisation founded to voice the views of its members so that the government of whatever political connection and society as a whole, understands the needs of business. Founded in 1965, the CBI is an independent, non-party political organisation funded entirely by its members in industry and commerce. The CBI’s objective is: ‘to help create and sustain the conditions in which business in the UK can compete and prosper.’

The CBI seeks to influence anybody – whether within government, around the UK regions, throughout Europe and beyond – to achieve this objective. Membership of the CBI is corporate – organisations and companies are members and not the individuals who represent them. Companies associated with the CBI, either directly or indirectly through trade associations, employ well over 10 million people.

The National Manufacturing Council (NMC)

Formed by the CBI in 1992, the National Manufacturing Council consists of representatives from approximately forty manufacturing companies, from large household names to small and medium sized businesses (SMEs). Since this time the

NMC has focused upon identifying the key strengths and weaknesses of UK manufacturing.

The NMC focuses on:

- building a partnership with Government to sustain an economic climate within which the manufacturing industry can prosper

- improving the status and image of manufacturing in the media, amongst policy makers, politicians, and young people who represent the UK’s future

- raising the performance levels of manufacturing by encouraging companies to share ‘best practice’ by benchmarking themselves against world class organisations.Benchmarking is a process which identifies the competencies of an organisation against the ‘best-in-class’.

Page 3: The importance of manufacturing to the economy

The UK has a long history of manufacturing dating back to the industrial revolution of the late nineteenth century when Britain was considered to be the workshop of the world. Historically, Britain’s manufacturing base was centred on heavy manufacturing industries such as shipbuilding. However, there has been a seismic shift in manufacturing over the last fifty years in terms of technological advancement. This has affected the ways in which goods are produced with new processes and automation.

The influence of manufacturing goes far beyond the direct contribution to national product and employment. Manufacturing is a global business underpinning all economic activity. Spending on goods accounts for more than half of all consumer expenditure, whilst manufacturing goods makes up around two-thirds of all UK exports. The UK workforce creates 4% of the world’s gross domestic product and 6% of the world’s exports, from a nation with one per cent of the world’s population.

Adding value

Essentially, value can be added to goods through:

- increasing the quality and specification of the product

- providing superior levels of service in providing the product

- enhancing the image of the product through marketing.

All these measures serve to differentiate the product from those offered by competitors. In the face of increasingly competitive markets and ever more demanding consumers, the ability to add value to products is crucial to future prosperity.

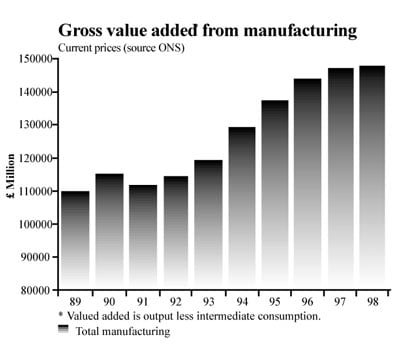

The importance of this is reflected in an increase in Gross Value Added from manufacturing in the UK. This figure has increased from £110,000 million in 1989 to around £148,000 million in 1997. Added value is at the heart of business activity – value is added at each stage of the production process. In order to remain competitive, companies need to be constantly innovating and responding to rapidly changing market needs. The value adding process is detailed within the figure below.

Market research will determine what customers want from the product. This will indicate if a demand exists and what the consumer wants in terms of features, specification, quality and price. There will then be a research and development phase which brings together the above demands, together with the technical possibilities

Before an innovative design can be put into full production, a prototype should be produced or testing of the product carried out. This increasingly involves the use of Computer Aided Design/Computer Aided Manufacturing (CAD/CAM) technology, allowing rapid changes to be made to the product. Stringent quality and safety tests must be undergone before production can fully commence. These may be in the form of recognised safety tests laid down by independent bodies, such as the British Standards Institute (BSI), or international standards, such as harmonised European standards.

Firstly, all raw materials must be obtained. This may be achieved through either producing the components or inputs – alternatively, they may be bought in from suppliers, who may be better placed to exploit economies of scale in this area.

Manufacturing the end product will ideally be achieved by lean production to ensure costly amounts of stock do not build up through the use of methods such as Just in Time. This approach also enables a rapid response to meet changing consumer demands. Much of the production process may now be automated, with repetitive tasks performed by machines.

Depending on the nature of the product, it may be supplied to the end consumer through direct sales from the factory – either through telephone-sales or the Internet – or more traditionally through retailers, who purchase larger quantities of the goods and act as ‘middle-men’. Retailers may also provide feedback to the manufacturer on the success of the product.

Ultimately, the product becomes available to the customer, who may choose to consume it, providing the product is close enough to the goods they demand – the specification identified by the market research.

An increasingly important method of adding value to manufactured products comes in the form of after-sales service. Such a facility enables the manufacturer to differentiate its product and offer products that are tailored to customer needs.

Overall, the company has taken a number of inputs including labour, raw material and components and has added value to those inputs through design, innovation, production and marketing.

The money the company receives from its customers will form its revenue; the money it pays to suppliers, its costs. The revenue received minus the costs will equate to the company’s profits. A percentage of the profit made will be liable for corporation tax, whilst some of it may be used to invest in the company, e.g. into the research of new products. The company might have plans for a new product range, requiring investment, design and planning before production can take place.

Global competition has placed knowledge-intensive businesses in the best position to prosper. UK manufacturers strive to innovate and add value to both products and services through enhanced design, technological innovation and new skills.

The distinction between manufacturing and services is therefore becoming blurred through service additions such as after-sales maintenance contracts, delivery, leases and finance options.

Many non-core activities, such as delivery of finished goods and logistics have been transferred from the manufacturers to specialised service providers. This also creates a strong and interdependent relationship between the sectors.

Manufacturing is vital to trade but can only realise its potential if it can embrace change and benchmark against best practice. This study emphasises the importance of manufacturing industries within the UK and the close ways in which they work with the service sector.

In a global marketplace where UK manufacturing companies face the full brunt of overseas competition, they can only succeed by being as good as the best within each market.