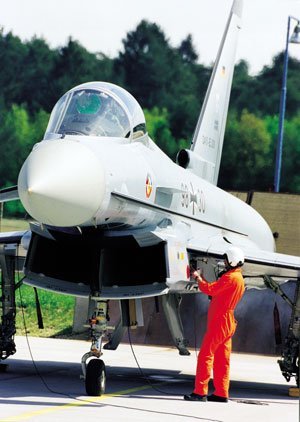

The Chiefs of Air Staff of Germany, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom signed an agreement to develop a new European fighter aircraft in January 1994. This agreement defined the requirement for an extremely agile, multi-role combat aircraft which could dominate the skies to the mid-21st Century, now called the Eurofighter Typhoon. Seven prototype development aircraft have been built and are undergoing an intensive flight test programme across the four countries.

It is clear that the Typhoon will be the world’s most advanced combat aircraft. Initial results seem to surpass all expectations. The aircraft is exceptionally agile, unrivalled in technology, highly manoeuvrable and has demonstrated its abilities in several spectacular flying displays, most recently at the 1999 Paris Air Show.

Several of the world’s air forces are interested in purchasing the aircraft and with production underway and orders for 620 aircraft already secured, the consortium members are confident of the success of the Eurofighter Typhoon. The first delivery of operational aircraft to the Air Forces of Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK is planned for 2002.

This case study looks at the strategies involved in developing and manufacturing a pan-European product.

Pan-European partnerships

The Eurofighter consortium consists of four industrial partners:

- British Aerospace, a world leader in aerospace and defence

- Alenia Aerospazio, the leading Italian manufacturer in the aerospace industry

- CASA, a Spanish company which is a world leader in materials development

- Daimler Chrysler Aerospace, a leading German aerospace manufacturer.

The partners agreed to divide the development, testing and production of the new fighter between themselves using facilities in each of the four countries, making this a genuinely pan-European project. The production work-share between the four countries was set according to each country’s planned purchase of the aircraft.

Therefore, Britain took on 37% of the production work in line with their planned orders for 232 aircraft, Germany 30% (180 aircraft), Italy 19% (121 aircraft) and Spain 14% (87 aircraft). Two separate groups were set up, one to develop the actual aircraft and the other to develop the EJ200 engine. The whole programme is managed by the NATO Eurofighter and Tornado Management Agency (NETMA).

Collaborative production

The production of something as technically complex as a fighter aircraft across four countries creates difficulties, but also offers tremendous benefits. The primary major advantage is that of cost because the substantial costs of development, which would in other circumstances be prohibitive to an individual country, are spread. This effectively reduces the risk involved to each partner. Without this collaboration, it is unlikely that any European country would unilaterally undertake such a project. The costs and risks would simply be too high and European air forces would be reliant on other countries for their aircraft. However, the collaboration of the requirements of four European NATO nations has resulted in an order for 620 aircraft – the largest production order for a military aircraft anywhere in the world.

Secondly, the four industrial partners can share their expertise in the aerospace industry. For instance, by sharing the technology used in work on commercial aircraft both products benefit from continual improvement in technology and materials. For example, CASA, the Spanish aerospace manufacturer has developed a high degree of specialisation in composite materials and is a world leader in the manufacturing of carbon fibre, an essential material in the Eurofighter’s construction.

The four partners have been involved in previous development projects and have built up their own areas of technological expertise. This wealth of technological knowledge is subsequently shared with the other partners to ensure cost-effective manufacturing. As this expertise is shared, it ensures that the aerospace industries of the partners will be world leaders with true global competitiveness.

The four partner companies will not only benefit from the technological challenges in the Eurofighter programme. There are around 400 first and second line suppliers – and thousands more suppliers beyond that – and 150,000 people who will be involved over the next 20 years at least, in the development and production of the Eurofighter Typhoon. It is believed this will create many positive benefits for the economy and, in particular, the industrial base of each of the member countries. However, the significance of the Eurofighter project is likely to have other important social and political implications – helping to cement international relations, strengthening the European defence pillar and its place in NATO.

The production contract established a maximum price for 620 aircraft worth $45 billion. These will be produced in three batches and Eurofighter is under obligation to reduce the unit cost of the aircraft with each batch, the ultimate and ambitious objective – to deliver the Typhoon at a lower average cost than the previous generation of fighters, the Tornado. If successful, this would be an unprecedented achievement as successive combat aircraft have always proved more expensive than their predecessors.

Managing the supply chain

British Aerospace and its partners know the penalties for failing with the Eurofighter project could be severe even as far as cancellation of the project. However, they recognised that it also represented a unique opportunity to develop and construct a new combat aircraft programme from the ground up, based on an entirely new business strategy.

Production is already underway in the four countries and the final assembly of the first aircraft commences in 2000 for delivery in 2001. Each country is responsible for producing particular sections of the aircraft; for example, the left wing is being built in Italy and the right wing in Spain. British Aerospace is manufacturing amongst other sections the front fuselage and the central and rear fuselage is being made in Germany. This specialisation creates considerable economies of scale and therefore lower unit costs.

The only duplication that will occur is in the final stages of production as each country undertakes the (final) assembly of its own aircraft. This will provide the infrastructure necessary in each nation to support the aircraft when in service with the Air Forces. This attention to cost has been forced on the production partners as the NATO defence budgets have shrunk since the end of the Cold War. Lean production techniques, which were developed in Japan and successfully applied to the western car industry during the 1980s, have been introduced at all the production centres.

Since British Aerospace has to buy in 70% of its raw materials from outside its own resources, the management of the industrial supply chain is of critical importance. Although having to rely on a myriad of suppliers is always a potentially high-risk area within such a project, it has also presented British Aerospace with an opportunity to transform its approach to production. The intention has been to move away from the traditional batch production methods and towards a regime called ‘one-piece flow’, a pull system from the customer right back to the suppliers of raw materials.

The factories operate a just-in-time approach to the control of stocks, with components arriving only when they are needed. Previously, these supplies had been delivered in batches because of unreliable forecasting techniques. Having inventory lying around on the factory floor, whether it be small components or fully assembled aircraft, resulted in much more cost to the manufacturer than the direct labour costs, long understood to be the cause of similar projects going over budget in the past.

New materials have been developed specifically for the Eurofighter, particularly carbon fibre composites and advanced alloys, which have demanded new standards in manufacturing. A £100 million investment programme has equipped British Aerospace with highly technical machinery, capable of delivering panels and fittings that are accurate to 70 microns (three thousand of an inch). This ‘right first time’ approach has reduced wastage and thereby further reduced the unit cost. It has also made fitting replacement parts and repairs much more straightforward, increasing the aircraft’s operational availability.

Almost every aspect of the aircraft’s performance was computer modelled before any of the prototypes took to the air. The extensive test flight programme has confirmed most of the computer predictions of the plane’s capabilities. The Kosovo conflict demonstrated that Europe did not have a true multi-role aircraft, and had to pass aircraft responsibilities to the US Air Force. Consequently, the Typhoon’s air-to-air and air-to-surface capabilities are eagerly awaited by the European Air Force.

Anticipating the future

The four consortium countries would clearly like to sell the aircraft to other countries’ Air Forces. Potential export sales of over 400 Aircraft are hoped for. This is an extremely competitive market and there will be many economic and political obstacles.

The first pilot from a potential new customer nation, Norway, has already completed a series of evaluation flights in one of the prototypes in 1999. Not only would Norway become a customer, but it would also be offered full participation in the Eurofighter programme, ensuring full access to all the technology used.

In April 1999, Greece confirmed its decision to join the Eurofighter programme, expressing an interest in procuring 60-90 Eurofighters. Interest has been expressed from as far and wide as Australia, South Korea, the Middle East and several European countries. The positioning and image of the product within this highly competitive market is extremely important.

Conclusion

The logistical, cultural and organisational problems that had to be overcome to achieve this level of collaboration and cooperation are substantial and history has not been on the Eurofighter’s side. Indeed there have been many twists and turns since 1979 when the development of a new multi-role fighter was first called for, as interested parties either expressed interest or dropped out before the four partners finally came to an agreement.

Many of these problems were as political as industrial, for example, the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, which plunged the initial negotiations into turmoil. Nevertheless, the partners are confident they will be able to fulfil their commitments, as production is now on target. This is likely to have long term implications for future projects involving collaboration and consortia in all fields, proving that pan-European cooperation can harness the expertise and deliver world beating results.

The Eurofighter project has so far proved to be a unique example of successful collaboration between companies and governments in a fiercely competitive world market for a high-technology defence product.