“Roy, the first shipment has just arrived, I thought you might like to see one.” Gary Maughan passed Roy Doughty a handset across the desk. Roy felt the weight of the phone and then opened the flip and laid the phone on the desk – “Terrific isn’t it?” He sat back and thought how far they’d come in the last three years. This case study tells the story of the design and development of the One 2 One handset.

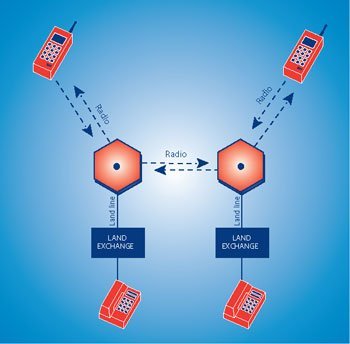

Mercury Personal Communications is a network service provider – giving the customer access to the two key components needed for the phone service – a handset and base station. MPC does not manufacture handsets itself, so this case study describes a model for new product development. A modern mobile phone network requires two key components to function – the handset and the base station. The handset transmits and receives calls and forms the interface with the user. This communicates by radio with a network of base stations which pass the call on to the fixed wire telephone network and to other users.

All change

Until the 1980s, the UK telecommunications industry was dominated by British Telecom (BT) the public utility company. However, in 1989 the government granted three licences to operate a Personal Communications Network (PCN), one of these was to Mercury Personal Communications (MPC) which today operates under the brand name One 2 One. Mercury Personal Communications launched One 2 One within four years of receiving its licence. MPC’s mission was:

“To be No 1 in the personal communications market, providing our customers with quality and innovative service.”

In other words, MPC was not only targeting the mobile phone market, but was also setting out to displace BT and to compete with satellite and cable services. The strategy was to provide a comprehensive personal communications service which appealed to a mass market and encouraged greater usage by being affordable and reliable whilst offering freedom, flexibility, convenience and control.

MPC understood the importance of creating a strong brand. Roy Doughty was appointed to develop brand values which would be reflected in all their products and services.

They were to be:

- owned by the user

- user friendly

- secure and personal

- widely available

- efficient

- affordable

- progressive

MPC’s design strategy was shaped by three major considerations. It had to take account of market research findings, fit in with the company’s overall business strategy and comply with regulatory requirements.

Market research – getting to know the customer.

MPC carried out market research which showed that:

- Consumers wanted to feel in control of the handset, yet were often unable to use all the functions of existing mobile phones.

- Pricing was critical, although customers understood that the handset price was only one component of the overall cost.

- There appeared to be a maximum acceptable size (300 cm) and weight (300 g), although some consumers felt sceptical about the capabilities of small handsets.

- Existing users were familiar with operating systems of traditional mobile phones.

In the light of this research, MPC forecast a 20% share of a market approaching 8 million subscribers by the year 1999/2000. They simulated a 400 user trial on an existing network to test the acceptability of a personal communications tariff. The results indicated an acceptance of the concept and the potential for trials to increase purchase intent.

Business strategy and regulatory requirements

A condition of the licence granted to MPC was that handsets be “type approved” by the Department of Trade and Industry and the British Approvals Board for Telecommunications.

Type approval was intended to make sure that equipment did not interfere with other telecommunications services. It also ensured that safety and comfort of the user were incorporated into the product. To be type approved, a handset had to pass up to 350 tests. The design of the handset in terms of its appearance, interface between the user and the machine and actual hardware all had to fulfil regulatory requirements.

MPC felt the handset should also have some brand image which would be transferable to future handsets produced by different manufacturers. Extra services such as voicemail, call divert, call wait and number storage needed to be easy to use, as these represented an effective way of increasing air traffic per consumer.

MPC saw the development of a unique One 2 One man-machine interface (MMI) as the best way of fostering an enduring brand identity. It could be flexible enough to be incorporated into other handsets produced by manufacturers with different approaches to design. A unique MMI as a retail concept, rather than colour schemes or bold graphics which could date rapidly, was clearly more sustainable.

Gary Maughan spoke to a large number of design consultancies about his needs. He was aware that there were restrictions on what could be done in industrial design terms because the handset would be based on an existing product. The emphasis on ease of use meant that the designer would need to develop the MMI of the handset while producing a new appearance to appeal to target consumers. The designer had to be prepared to work closely with MPC.

Gary chose IDEO as being the most suitable consultancy. IDEO was a multidisciplinary group comprising industrial designers, engineers and human factor specialists. Their approach and strength involved studying consumers actually using products.

The design brief

At the first meeting, Gary presented a broad description of One 2 One’s brand values and the design strategy of the project. At this stage he had no specific written brief – just an overall explanation of the aims and requirements. Targets for volumes and prices were not fixed. Further meetings led to the development of a product idea.

A year after the first meeting with IDEO, Gary visited the proposed manufacturer with the two IDEO designers: Marc Tanner – responsible for industrial design and the project as a whole and Peter Spreenburg – responsible for interface design.

During the first meeting with the manufacturer, much of the discussion centred on design constraints. Although the manufacturer was unwilling to make significant changes to the existing unit (the position of the power switch and antenna), the designers were keen to see what scope there was for change, for example, the finish of the plastics used and the shape of keypad buttons. The meeting had no clear outcomes. Gary decided to adopt an approach which assumed that anything could be changed and instructed IDEO to work on that basis.

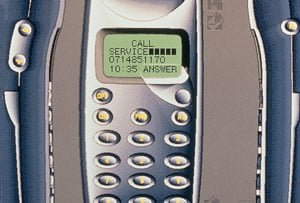

The second meeting with the manufacturer was a fortnight later and the pressure was intense. Communication between MPC and IDEO was frequent and informal. Gary and Marc returned to the manufacturer with a basis for the interface design relying on a single prominent “soft key,” this would form the major interface between the user and a menu system. The key was initially to be placed inside the LCD display area and the operating system of the phone would be assigned to the user’s most likely next action. The display would use a text message next to the key to describe its action – for example if the user entered a number the phone’s operating system would assume that the user wanted to call that number and the word “CALL” would appear next to the soft key. Pressing the key would cause the phone to dial the number entered.

Marc presented eight possible visual themes for the phone and these were discussed in turn. Features that worked well were highlighted and those that did not were rejected. Two were eventually chosen to form the basis for further work, though features from some of the rejected designs were to be incorporated later. The display proved to be a major discussion point. Gary and Marc wanted a more complex display than the manufacturer had used previously, with smaller icons and text to enable more information to be presented – this was essential for the viability of the proposed interface design. The manufacturer resisted the change at first, citing their previous problems with legibility. After considerable technical discussion the manufacturer was persuaded and the complex display was approved.

Refining the design

Two months were spent refining the design. The design and engineering of the handset was to be carried out by the manufacturer’s own industrial designers but in close consultation with IDEO. During this period one of the manufacturer’s industrial designers called on IDEO. During the visit it became clear that the manufacturer would only allow flexibility in design of the front moulding/keys and flip. This would place a constraint on the design and would severely limit the opportunities of achieving the preferred design direction. Marc and Gary therefore agreed that IDEO would develop two main “families” – with and without these restrictions. Gary wanted to continue pressurising the manufacturer’s own designers to be more visionary.

The next step was to produce a “virtual prototype” ie a virtual presentation of the phone on a computer screen. This was much cheaper and quicker than producing an actual prototype. By using the PC’s mouse to locate and “press” the buttons on the phone’s keypad, a user could utilise all the phone’s functions. The display changed on the screen to mimic the actual phone and sampled sounds completed the model by simulating dialling tones etc.

The next stage was to check that the design features were appropriate and valued by potential consumers. Trials were carried out on a test sample of consumers. Test participants were required to make a call, access the phone’s directory system and store a name and number in the phone’s memory. To make the test more realistic, participants were given no instructions and so were entirely reliant on the phone’s interface.

Whilst all of the above was taking place, MPC was agreeing the terms of a contract with the manufacturer. This was a difficult task for both parties as some of the details of the final design were unknown. The contract was eventually to stipulate prices, schedules and minimum production volumes. MPC agreed to give the manufacturer ownership of the industrial design of the phone, while MPC would retain ownership of the interface, ensuring that it could be used on future handsets from other manufacturers. IDEO gave their completed design work to the manufacturer. It included the three dimensional block models and Computer Aided Design drawing, the computer simulation and a document describing the interface in more detail. This ended IDEOs involvement in the project.

The manufacturer’s software engineers took the IDEO/MPC design work and began to interpret it in order to define the phone’s software specification and plan its production. This work required intense communication between MPC and the manufacturer. The handset’s design incorporated a battery and accessory pack identical to the manufacturer’s other products. This meant that the overall form of the phone was virtually unchanged from the handset on whose technology the One 2 One item was based. As Terry Taylor – the manufacturer’s industrial designer explained “MPC had an image in mind and brought in an outside designer. We received sketches from them relating the general feel that they wanted, but it didn’t relate to our technology base. The elliptical theme and MMI in these proposals did give the unit its character though and they also were responsible for the colours and graphics of the unit. We actually went through several iterations with MPC giving their input before completing the final model.”

Tooling and testing

The manufacturer now set about tooling up for production in bulk, using CAD and computer simulations. Twelve months after the first speculative ideas were sketched, the first components were produced. Accelerated life testing was used to simulate the phone’s usage over its lifetime and to prove its durability under all climatic conditions.

Gary’s role now changed from that of product champion and innovator to that of project manager. He was responsible for ensuring that production took place as planned and to schedule, liaising between engineers of the handset, network manufacturer and within MPC.

Mercury wanted a number of phones to be produced quickly so that they could be tested “for real” using their existing network. The initial testing caused a number of complications because there were so many technological unknowns. Throughout the testing procedures, MPC was also negotiating type approval from the DTI. An interim approval was obtained in time for the planned launch, though final approval was not due to be given until the network was fully operational.

Gary contemplated the future. Production of the handset was up to target and stocks were in place with distributors ready for launch. He had been involved in the development of a £10 million promotional campaign to support the launch of One 2 One and customer services were ready for the expected influx of subscribers. An innovative tariff structure had been agreed, including the offer of free off peak local calls – a first in the UK. However, would consumers like the phone and would they use it enough to generate the revenues the company required to make a profit? The ease of use and market acceptability of the phone would be a key factor. Had he got it right?